1921 emergency quota act

Hello. Welcome to solsarin. This post is about “1921 emergency quota act“.

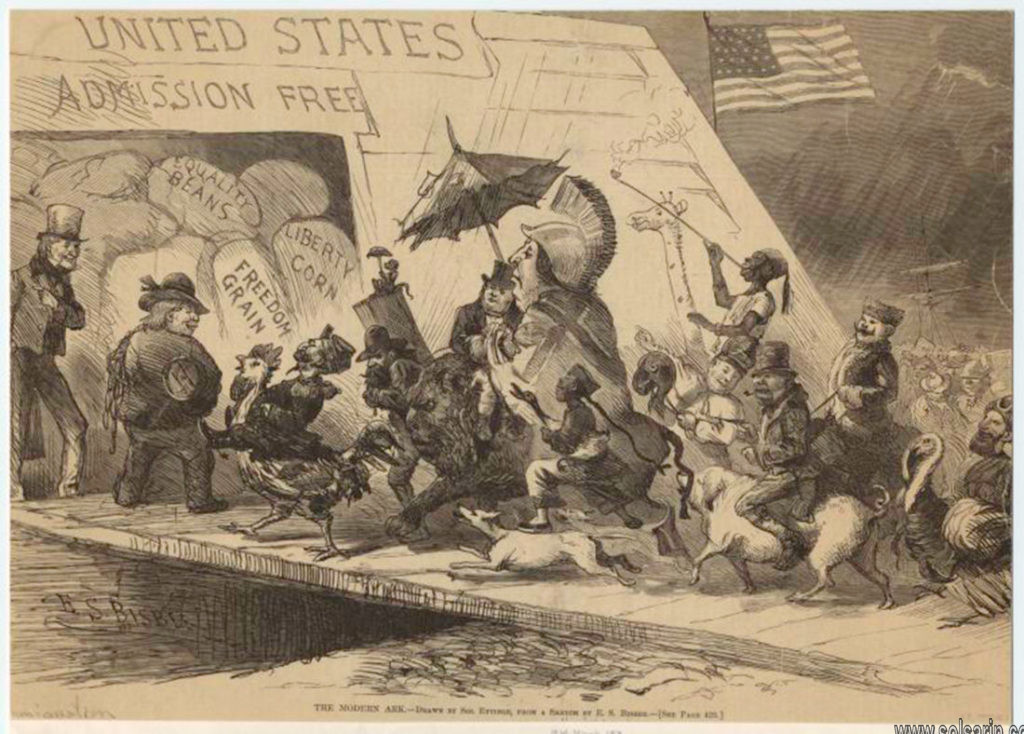

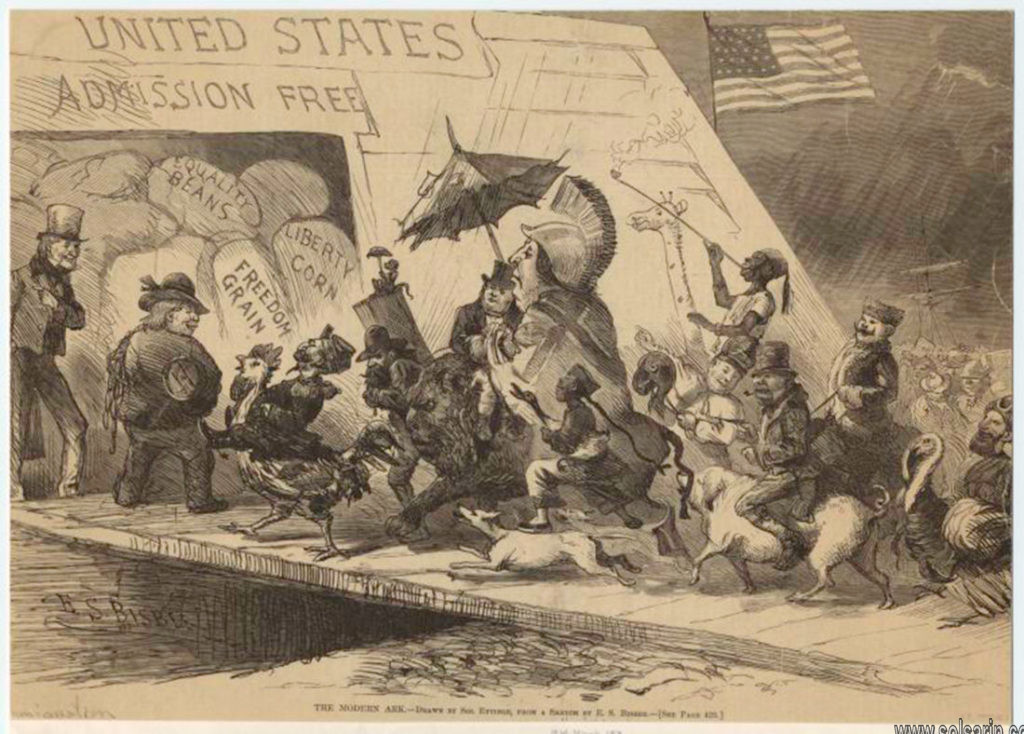

Land of the Free?

America is a land of immigrants. Does your heritage involve someone coming here from another country? If so, many people can relate to you. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the United States witnessed a boom in the number of people coming from other countries, also called immigrants. The quantity of those who came was as numerous as their reasons for coming.

Despite our nation tempting immigrants with the American Dream, the U.S. government began restricting the quantity of those who could come into the country. This was done through the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act and Immigration Restriction Act. This act restricted the number of new immigrants per year to 3 percent of the number of residents from that country already in the U.S. Let’s examine the basis of the act, why it was passed, and the impact it left.

Background on Immigration

To understand the Emergency Quota Act, one has to know why there were so many immigrants in the first place. Beginning with the Pilgrims (the first settlers) in 1620, religious freedom has always been a reason to come to America. Some also came for better economic opportunities, such as during the Gold Rush, while others simply wanted a better quality of life. Europe in the 1880s through 1920s was not a great place to be, given World War I and other conflicts. Millions would come, especially during the height of immigration from approximately 1880 to 1920.

Emergency Quota Act

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, 42 Stat. 5 of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the large influx of Southern and Eastern Europeans and successfully restricted their immigration as well as that of other “undesirables” to the United States.

Although intended as temporary legislation, it “proved, in the long run, the most important turning-point in American immigration policy” because it added two new features to American immigration law: numerical limits on immigration and the use of a quota system for establishing those limits, which came to be known as the National Origins Formula.

1910

The Emergency Quota Act restricted the number of immigrants admitted from any country annually to 3% of the number of residents from that country living in the United States as of the 1910 Census. That meant that people from Northern and Western Europe had a higher quota and were more likely to be admitted to the US than those from Eastern or Southern Europe or from non-European countries.

The act did not apply to countries with bilateral agreements with the US or to Asian countries listed in the Immigration Act of 1917, known as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act.

2% of countries’ representation

The Immigration Act of 1924 reduced the quota to 2% of countries’ representation in the 1890 census, when a fairly small percentage of the population was from the regions that were regarded as less than desirable. It mandated all non-citizens seeking to enter the US to obtain and present a visa obtained from a US embassy or consulate before they arrived to the US.

Immigration inspectors handled the visa packets depending on whether they were non-immigrant (visitor) or immigrant (permanent admission). Non-immigrant visas were kept at the ports of entry and were later destroyed, but immigrant visas were sent to the Central Office, in Washington, DC, for processing and filing.

Based on the formula, the number of new immigrants admitted fell from 805,228 in 1920 to 309,556 in 1921-22. The average annual inflow of immigrants prior to 1921 was 175,983 from Northern and Western Europe and 685,531 from other countries, mainly Southern and Eastern Europe. In 1921, there was a drastic reduction in immigration levels from other countries, principally Southern and Eastern Europe.

1965

After the end of World War I, both Europe and the United States were experiencing economic and social upheaval. In Europe, the war’s destruction, the Russian Revolution, and the dissolutions of both the Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire led to an increase of immigration to the United States. In the US, an economic downturn after the postwar demobilization increased unemployment. The combination of increased immigration from Europe at the time of higher American unemployment strengthened the anti-immigrant movement.

The act, sponsored by US Representative Albert Johnson (R-Washington), was passed without a recorded vote in the US House of Representatives and by a vote of 90-2-4 in the US Senate.

Introduction

The Immigration Act of 1924 limited the number of immigrants allowed entry into the United States through a national origins quota. The quota provided immigration visas to two percent of the total number of people of each nationality in the United States as of the 1890 national census. It completely excluded immigrants from Asia.

Literacy Tests and “Asiatic Barred Zone”

In 1917, the U.S. Congress enacted the first widely restrictive immigration law. The uncertainty generated over national security during World War I made it possible for Congress to pass this legislation, and it included several important provisions that paved the way for the 1924 Act. The 1917 Act implemented a literacy test that required immigrants over 16 years old to demonstrate basic reading comprehension in any language.

1907

It also increased the tax paid by new immigrants upon arrival and allowed immigration officials to exercise more discretion in making decisions over whom to exclude. Finally, the Act excluded from entry anyone born in a geographically defined “Asiatic Barred Zone” except for Japanese and Filipinos. In 1907, the Japanese Government had voluntarily limited Japanese immigration to the United States in the Gentlemen’s Agreement. The Philippines was a U.S. colony, so its citizens were U.S. nationals and could travel freely to the United States.

Immigration Quotas

The literacy test alone was not enough to prevent most potential immigrants from entering, so members of Congress sought a new way to restrict immigration in the 1920s. Immigration expert and Republican Senator from Vermont William P. Dillingham introduced a measure to create immigration quotas, which he set at three percent of the total population of the foreign-born of each nationality in the United States as recorded in the 1910 census.

This put the total number of visas available each year to new immigrants at 350,000. It did not, however, establish quotas of any kind for residents of the Western Hemisphere. President Wilson opposed the restrictive act, preferring a more liberal immigration policy, so he used the pocket veto to prevent its passage. In early 1921, the newly inaugurated President Warren Harding called Congress back to a special session to pass the law.

From 1910 to 1890

Though there were advocates for raising quotas and allowing more people to enter, the champions of restriction triumphed. They created a plan that lowered the existing quota from three to two percent of the foreign-born population. They also pushed back the year on which quota calculations were based from 1910 to 1890.

100 Years Later

May 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, the first immigration law in the United States to establish an immigration quota system based on national origins. As the “emergency” in its name suggests, the act was part of the American reaction to the immense tumult that accompanied the end of the first World War. It reflected a broader effort at retrenchment in the face of change, a quest for “normalcy,” in the words of victorious 1920 presidential candidate Warren G. Harding.

Yet a long-gestating effort to restrict the immigration that accompanied the immense economic changes of the industrial revolution preceded the act. For years, disparate but at times overlapping groups inspired by labor concerns, anti-Catholicism, and pseudoscientific racial “science” had all perceived this immigration as a potential threat.

1882

The intertwined concerns over race and labor can be seen in a predecessor to the Emergency Quota Act, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The Exclusion Act took aim at Chinese labor, although distinguishing between laborers and non-laborers was difficult and often reflected racial assumptions on the part of those doing the distinguishing.

The eventual success of this exclusion campaign, however, did not deter the millions of immigrants arriving from southern and eastern Europe in the 1800s and early 1900s. While anti-Chinese sentiment was particularly strident, other labor leaders, such as the American Federation of Labor’s Samuel Gompers, agitated against unrestricted immigration in general, for fear of its effect on wages. Like Kearney, Gompers was himself an immigrant. However, for several reasons, Gompers viewed the “new” immigrants in the 1890s and 1900s as outside of the natural constituency of skilled laborers that the AFL worked to unionize.

IWW

Differences in language and culture also inhibited organization. The International Workers of the World (IWW) did attempt to organize across skill-level and national lines, but this connection with the more radical of the labor unions contributed to the association of immigrants with political danger.

Suspecting Catholics of allegiance to an outside power (the Pope), the American Protective Association railed against Catholic schools as a subversive threat to American democracy. The rejuvenated Ku Klux Klan, which spread beyond the former Confederacy as a political force in the 1910s and 1920s, also defined itself on its opposition to Catholicism in addition to its commitment to white supremacy.

Science

Also supporting restriction were believers in the “science” that undergirded the eugenics movement, which held national identity as a racial feature. Perhaps most infamous of these was Madison Grant, who warned in The Passing of the Great Race (1916) that new immigrants from places like Poland or Italy could never assimilate to U.S. society and that “native Americans” – that is, largely Protestant, white Americans who traced their ancestry to northern and western Europe – would face an existential risk of destruction.

Grant predicted that “in large sections of the country the native Americans will entirely disappear . . . New York is becoming a cloaca gentium [sewer of nations] which will produce many amazing racial hybrids and some ethnic horrors that will be beyond the powers of future anthropologists to unravel.”

Thank you for staying with this post “1921 emergency quota act” until the end.