children of william the conqueror

Hi,welcomw to solsarin site,today we want to talk about“children of william the conqueror”,thank you for choosing us.

children of william the conqueror,

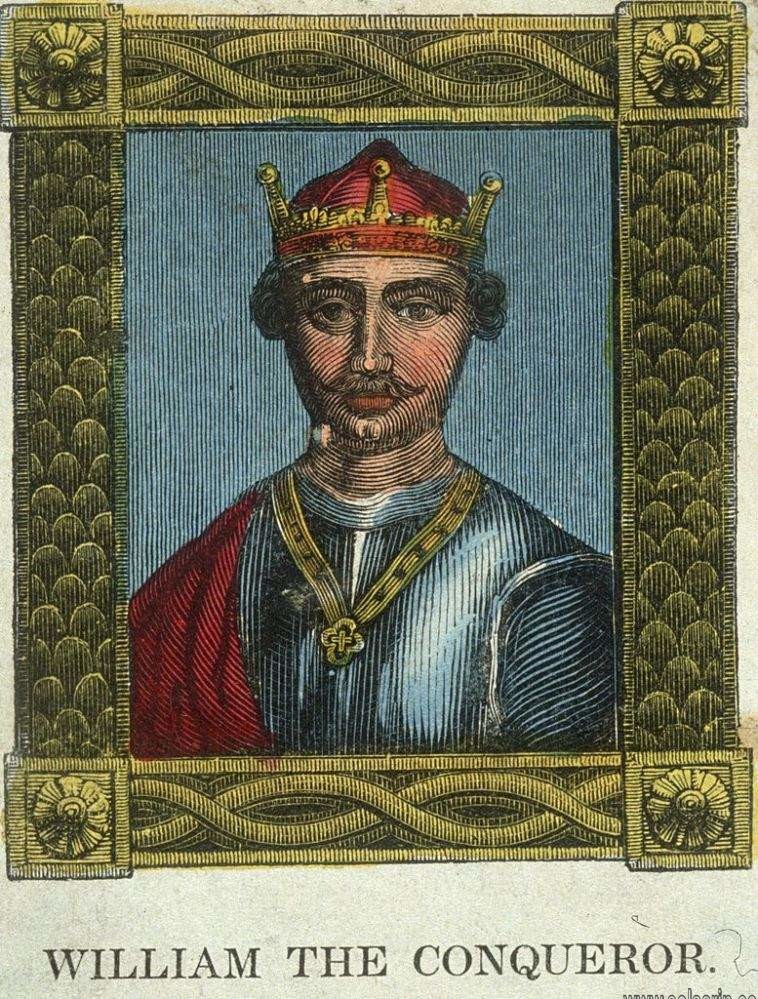

Who Was William the Conqueror?

At the age of eight, William the Conqueror became duke of Normandy and later King of England. Violence plagued his early reign, but with the help of King Henry I of France, William managed to survive the early years. After the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, he was crowned king of England. He never spoke English and was illiterate, but he had more influence on the evolution of the English language then anyone before or since. William ruled England until his death, on September 9, 1087, in Rouen, France.

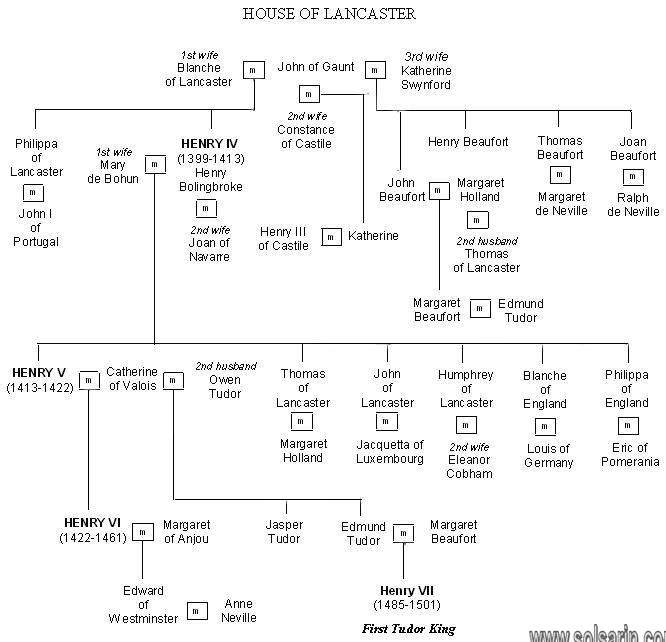

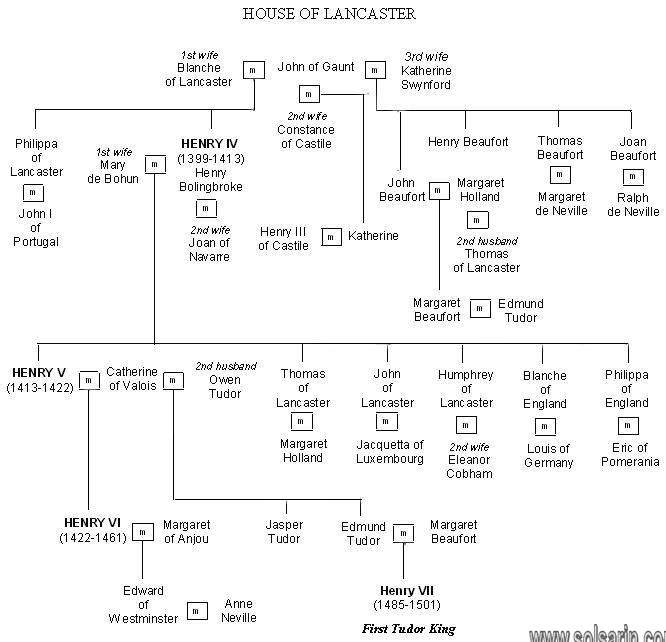

William the Conqueror had four sons and five daughters, and every monarch of England since has been his direct descendant.

Early years

William was the elder of the two children of Robert I of Normandy and his concubine Herleva (also called Arlette, the daughter of a tanner or undertaker from the town of Falaise). Sometime after William’s birth, Herleva was married to Herluin, viscount of Conteville, by whom she bore two sons—including Odo, the future bishop of Bayeux—and at least one daughter. In 1035 Robert died while returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and William, his only son, whom he had nominated as his heir before his departure, was accepted as duke by the Norman magnates and by his overlord, King Henry I of France.

William and his friends had to overcome enormous obstacles, including William’s illegitimacy (he was generally known as the Bastard) and the fact that he had acceded as a child. His weakness led to a breakdown of authority throughout the duchy: private castles were erected, public power was usurped by lesser nobles, and private warfare broke out.

Three of William’s guardians died violent deaths before he grew up, and his tutor was murdered. His father’s kin were of little help, since most of them thought that they stood to gain by the boy’s death. His mother, however, managed to protect him through the most dangerous period. These early difficulties probably contributed to William’s strength of purpose and his dislike of lawlessness and misrule.

children

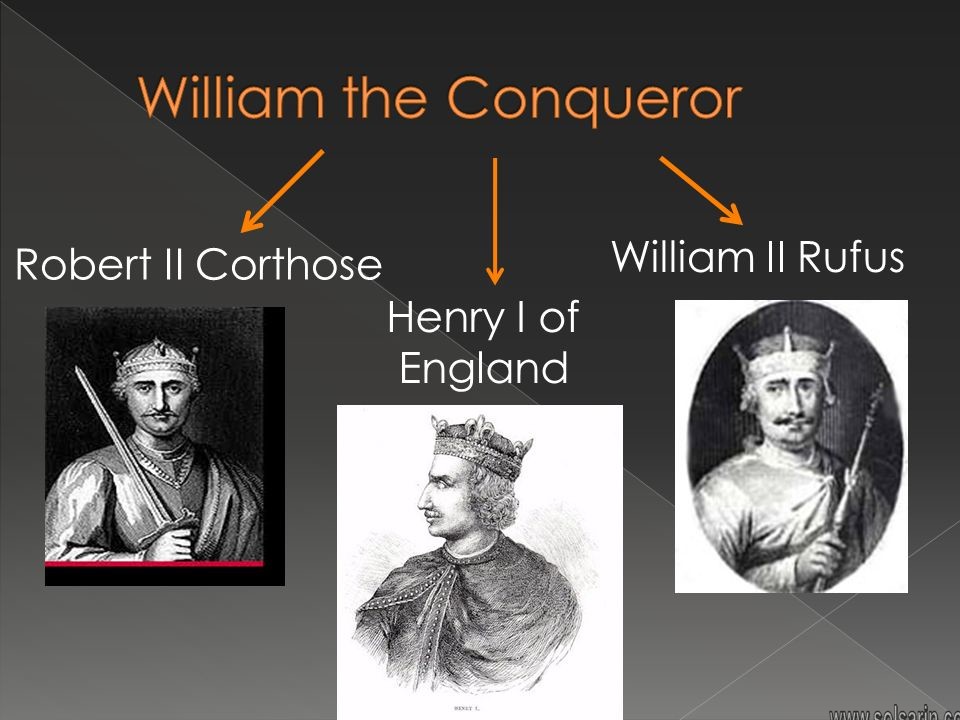

William the Conqueror sired 4 sons, three of whom were alive at the time of his death in 1087.

Two became kings, another was a crusading duke; all three fought for the right to rule over the Anglo-Norman realm their father created.

Robert II, Duke of Normandy (c. 1501-1134)

The eldest was Robert, dubbed with the sobriquet ‘Curthose’ (colloquially, ‘shorty’).

Given his prowess as a knight – he was a hero of the First Crusade – the nickname could never have been used to his face without blows being exchanged.

He had once rebelled and defeated his father in combat, wounding and unhorsing him at the Battle of Gerberoy in the winter of 1078-9.

William for a time afterwards had wanted to disown Robert entirely, but was unable to: his son’s claim to the dukedom of Normandy had in the past been underwritten by the great and good of the duchy, who remained politically and morally invested in Robert as their duke-in-waiting.

Interaction between father and son, nevertheless, remained problematic right up until William’s passing. Although a mere two or three days’ ride away at Abbeville, Robert did not attend William’s deathbed or funeral.

The snub may not have been deliberate: he might have been unaware of his father’s plight, kept in the dark by his younger brothers so that they could better progress their own agendas.

William II, King of England (c. 1056-1100)

William II, byname William Rufus, French Guillaume Le Roux, (born c. 1056—died August 2, 1100, near Lyndhurst, Hampshire, England), son of William I the Conqueror and King of England from 1087 to 1100; he was also de facto duke of Normandy (as William III) from 1096 to 1100. He prevented the dissolution of political ties between England and Normandy, but his strong-armed rule earned him a reputation as a brutal, corrupt tyrant. Rufus (“the Red”—so named for his ruddy complexion) was William’s third (second surviving) and favourite son. In accordance with feudal custom, William I bequeathed his inheritance, the Duchy of Normandy, to his eldest son, Robert II Curthose; England, William’s kingdom by conquest, was given to Rufus.

Nevertheless, many Norman barons in England wanted England and Normandy to remain under one ruler, and shortly after Rufus succeeded to the throne, they conspired to overthrow him in favour of Robert. Led by the Conqueror’s half brother, Odo of Bayeux, Earl of Kent, they raised rebellions in eastern England in 1088. Rufus immediately won the native English to his side by pledging to cut taxes and institute efficient government. The insurgency was suppressed, but the king failed to keep his promises.

Consequently, a second baronial revolt, led by Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland, broke out in 1095. This time William punished the ringleaders with such brutality that no barons dared to challenge his authority thereafter. His attempts to undermine the authority of the English church provoked resistance from St. Anselm, archbishop of Canterbury, who, defeated, left the country for Rome in 1097; Rufus immediately seized the lands of Canterbury.

Henry I, King of England (c. 1068-1135)

king of England (1100–35) and duke of Normandy (1106–35), was the youngest son of William the Conqueror. In 1087, on his death-bed, William had given Henry a large sum of money, which he used to purchase land in Normandy.

He played an intermittent role in the struggle between his elder brothers Robert Curthose and William Rufus for control of the Anglo-Norman realm and seized the opportunity provided by the latter’s (probably) accidental death in 1100 to take over the English kingdom while Robert was still on his return journey from the First Crusade. Henry moved quickly to consolidate his coup,

issuing a coronation charter which promised to renounce the supposed abuses of William II’s rule, recalling Archbishop Anselm from exile,

and marrying Matilda, the niece of Edgar the Atheling and the daughter of Malcolm Canmore,

to create a dynastic link with the Old English ruling house and an alliance with the kingdom of Scots.

By 1101 he was sufficiently powerful to resist Robert’s invasion of England and to agree terms with him which confirmed Henry’s kingship in England. Thus established,

Henry then proceeded to disinherit a number of powerful magnates known to be supporters of Robert’s cause and to

undermine his brother’s already precarious authority in Normandy. In 1105–6 he invaded Normandy and completed

his conquest of the duchy by defeating Robert in 1106 at the battle of Tinchebrai, thereby recreating William the Conqueror’s Anglo-Norman realm.

HenryI

Henry ruled both England and Normandy for the rest of his life, but his control over Normandy was always threatened until the death of Robert’s son William Clito in 1128 by alliances between William, the French king Louis VI, territorial princes such as the counts of Flanders and Anjou, and a group of Norman nobles with few landed interests in England. Henry suffered set-backs such as a military defeat at Alençon in 1119, but was successful in defeating invasions of Normandy in 1118–19 and 1123–4. Marriage alliances were used to secure useful allies, such as the one between his nephew, the future King Stephen, and Matilda, the heiress to the county of Boulogne.

The death of his only legitimate son in the White Ship disaster increased Henry’s problems and his failure to obtain an heir through his second marriage to Adela of Louvain eventually forced him to the apparently desperate measure of marrying his daughter, the Empress Matilda, to Count Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou in 1128, thereby neutralizing one of his most powerful opponents at the cost of the prospect of an Angevin succession to England and Normandy after Henry’s death.

first marriage

On 11 November 1100 Henry married Edith, daughter of King Malcolm III. Since Edith was also the niece of Edgar Atheling and the great-granddaughter of Edward the Confessor’s paternal half-brother Edmund Ironside,

the marriage united the Norman line with the old English line of Kings. The marriage greatly displeased the Norman Barons, however,

and as a concession to their sensibilities Edith changed her name to Matilda upon becoming Queen. The other side of this coin, however,

was that Henry, by dint of his marriage, became far more acceptable to the Anglo-Saxon populace.

The Chronicler William of Malmesbury described Henry thus: “He was of middle stature,

greater than the small, but exceeded by the very tall; his hair was black and set back upon the forehead; his eyes mildly bright and chest brawny and body fleshy.”

Second marriage

On 29 January 1121, he married Adeliza, daughter of Godfrey I of Leuven,

Duke of Lower Lotharingia and Landgrave of Brabant, but there were no children from this marriage. Left without male heirs, Henry took the unprecedented step of making his barons swear to accept his daughter Empress Matilda,

widow of Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor, as his heir.

Activities as a King

Henry’s need for finance to consolidate his position led to an increase in the activities of centralized government. As King, Henry carried out social and judicial reforms, including:

- issuing the Charter of Liberties

- restoring the laws of King Edward the Confessor.

Henry was also known for some brutal acts. He once threw a traitorous burgher named Conan Pilatus from the tower of Rouen; the tower was known from then on as “Conan’s Leap”. In another instance that took place in 1119,

Henry’s son-in-law, Eustace de Pacy, and Ralph Harnec, the constable of Ivry, exchanged their children as hostages. When Eustace blinded Harnec’s son, Harnec demanded vengeance. King Henry allowed Harnec to blind and mutilate Eustace’s two daughters, who were also Henry’s own grandchildren. Eustace and his wife, Juliane, were outraged and threatened to rebel. Henry arranged to meet his daughter at a parley at Breteuil,

only for Juliane to draw a crossbow and attempt to assassinate her father. She was captured and confined to the castle, but escaped by leaping from a window into the moat below. Some years later Henry was reconciled with his daughter and son-in-law.