did wyatt earp have children?

Hi, welcome to solsarin site, today we want to talk about“did wyatt earp have children”,

thank you for choosing us.

did wyatt earp have children?

Who Was Wyatt Earp?

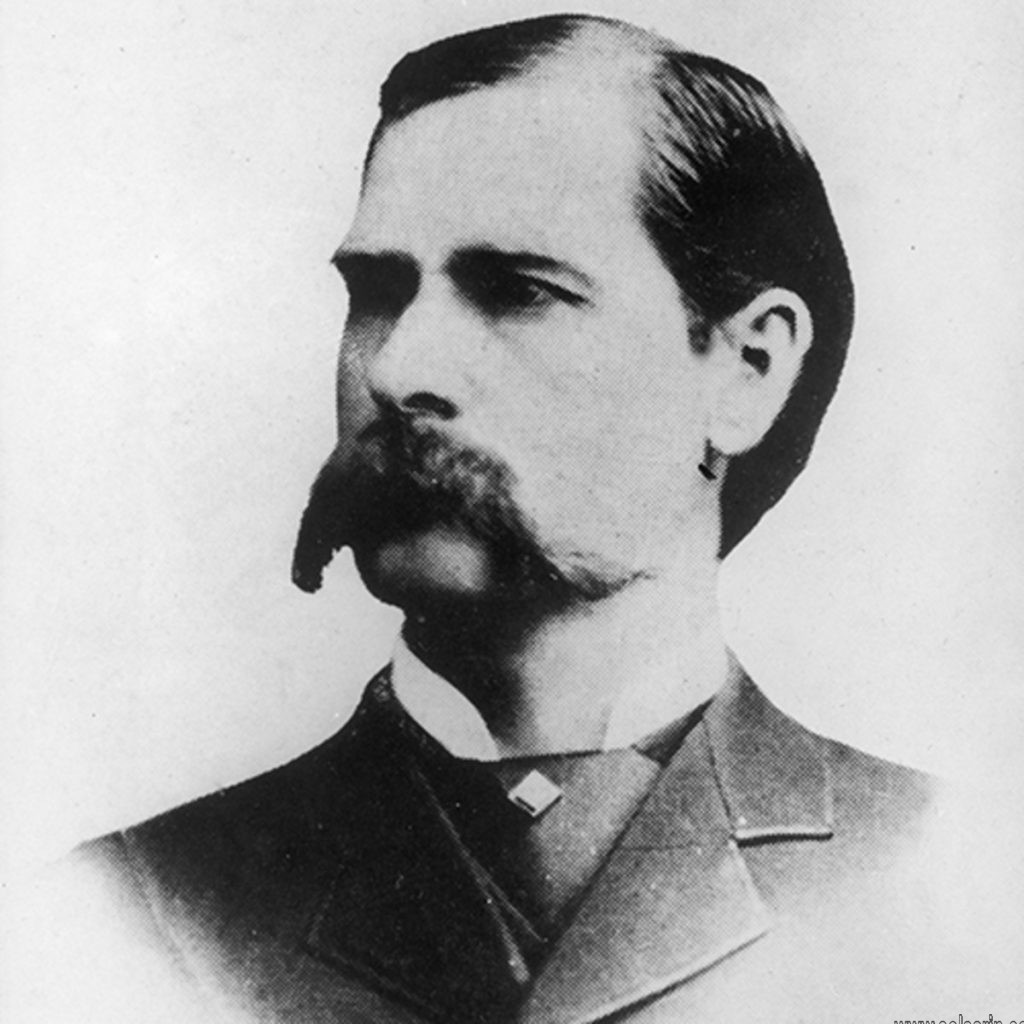

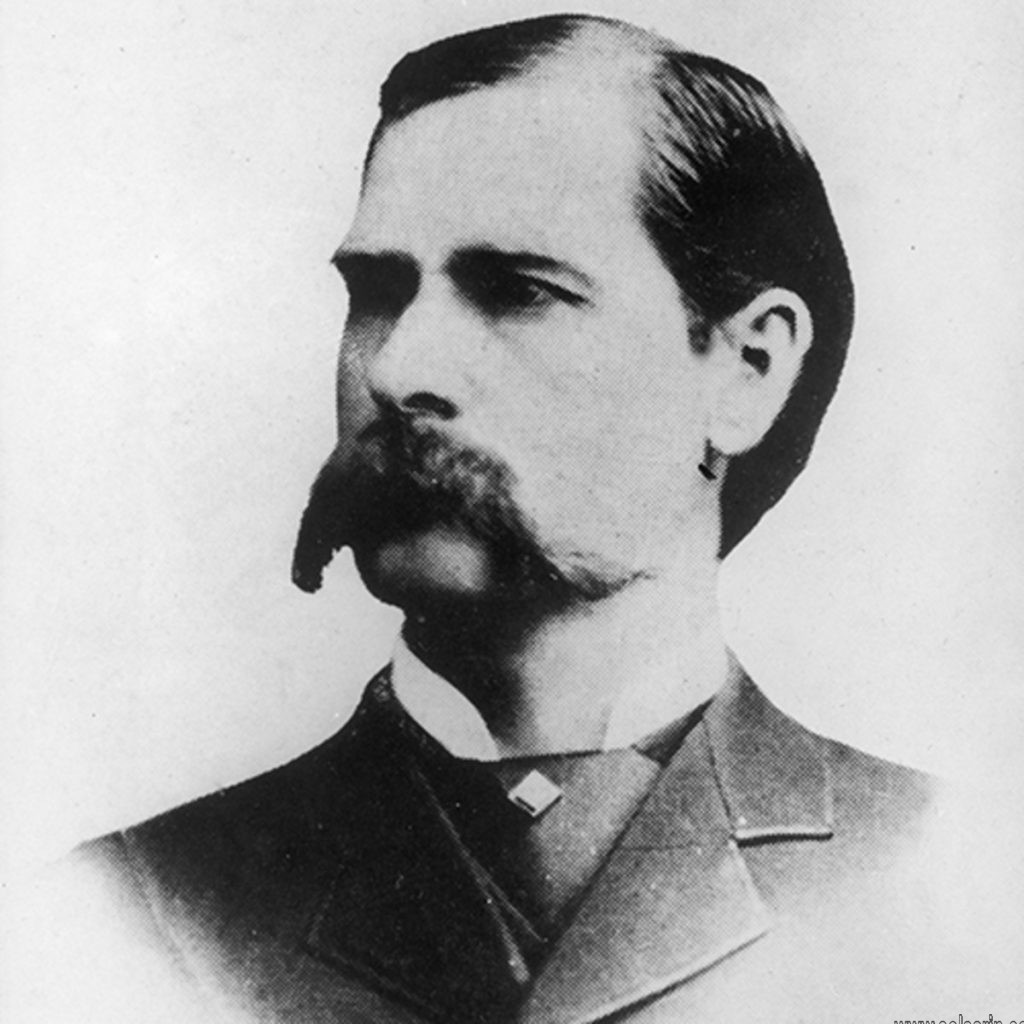

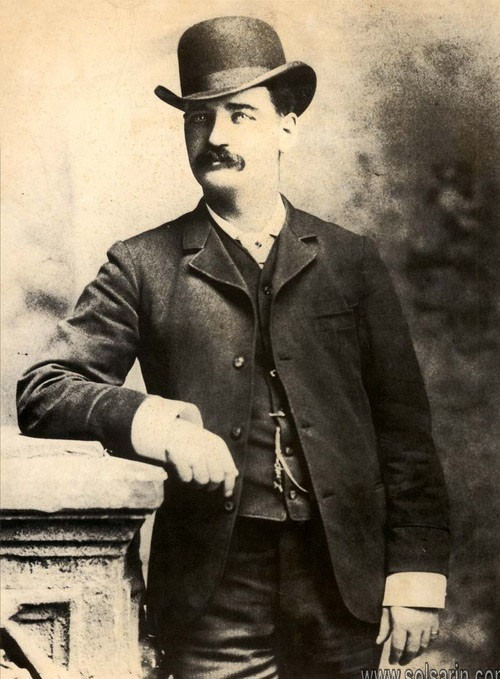

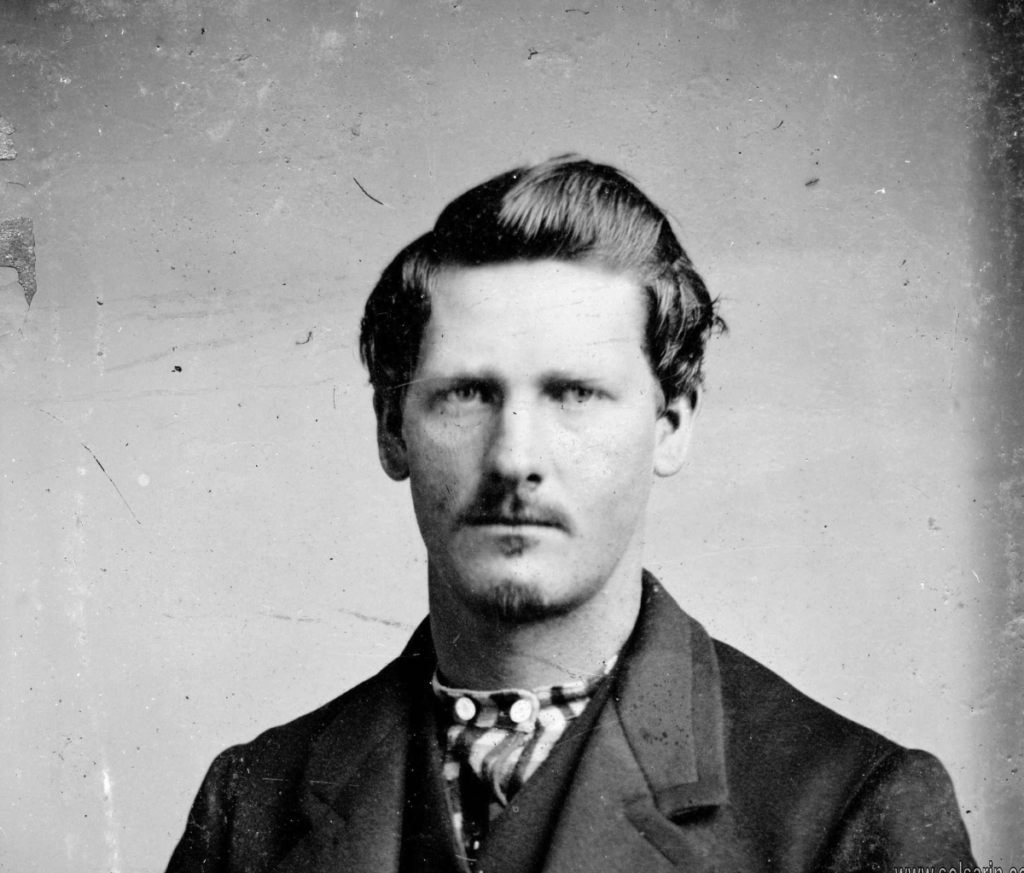

Wyatt Earp, in full Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp, (born March 19, 1848, Monmouth, Illinois, U.S.—died January 13, 1929, Los Angeles, California), legendary frontiersman of the American West, who was an itinerant saloonkeeper, gambler, lawman, gunslinger, and confidence man but was perhaps best known for his involvement in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1881). The first major biography, Stuart N. Lake’s Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal (1931), written with Earp’s collaboration, established the rather fictionalized portrait of a fearless lawman.

Earp was the fourth of eight children born to Nicholas Earp and his second wife, Virginia Ann Cooksey. His four brothers—James (1841–1926), Virgil (1843–1905), Morgan (1851–82), and Warren (1855–1900)—as well as a half-brother, Newton, would play integral roles throughout Wyatt’s life. He grew up in Illinois and Iowa but in 1864, toward the end of the American Civil War, his family moved to an area near San Bernardino, California. In 1868 most of the Earps returned to Illinois via the Union Pacific Railroad, on which Wyatt and Virgil lingered to work in what is now Wyoming.

What happened to the Earp family?

Warren Earp, the youngest of the famous clan of gun fighting brothers, is murdered in an Arizona saloon. Nicholas and Virginia Earp raised a family of five sons and four daughters on a series of farms in Illinois and Iowa. Three of the Earps’ sons grew up to win lasting infamy.

Did any of the Earp siblings have kids?

Wyatt and Josie had no children. In fact none of the “Fighting Earps”—Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan and Warren—had any sons. Virgil did have a daughter from his first marriage.

How many family members did Wyatt Earp have?

seven

Wyatt had seven full siblings — James, Virgil, Martha, Morgan, Warren, Virginia, and Adelia — as well as an elder half-brother, Newton, from his father’s first marriage.

When did Wyatt Earp get married?

1882 (Josephine Earp)

1878 (Mattie Blaylock)January 10, 1870 (Urilla Sutherland)

Wyatt Earp/Wedding dates

When did Sadie Frost and Wyatt Earp get married?

By the summer of 1882, Sadie was married to Wyatt Earp, the famous gambler and deputy sheriff, who would lead the most famous shootout in the history of the American Wild West. The ceremony allegedly took place on a yacht off the California coast but no public record of their marriage has ever been found.

Man of the West

Broken and devastated by his wife’s death, Earp left Lamar and set off on a new life devoid of any kind of grounding. In Arkansas, he was arrested for stealing a horse but managed to avoid punishment by escaping from his jail cell. moreover, For the next several years, Earp roamed the frontier, making his home in saloons and brothels, working as a strongman and befriending several different prostitutes.

In 1876, he moved to Wichita, Kansas, where his brother Virgil had opened a new brothel that catered to the cowboys coming off their long cattle drives. There, he also began working with a part-time police officer on rounding up criminals.

But while he had reinvented himself as a lawman, the speculative spirit that had driven his father ran in Earp as well. In December 1879, Earp joined his brothers Virgil and Morgan in Tombstone, Arizona, a booming frontier town that had only recently been erected when a speculator discovered the land there contained vast amounts of silver. His good friend Doc Holliday, whom he’d met in Kansas, joined him.

But the silver riches the Earp brothers hoped to find never came, forcing Earp begrudgingly to return to law work. In a town and a region desperate to tame the lawlessness of the cowboy culture that pervaded the frontier, Earp was a welcome sight.

Differing Views of Wyatt Earp

Earp belongs in the pantheon of popular western heroes and villains,

alongside names made famous in history texts, fiction, folk song, theater, musical comedy, film, and television. His contemporaries included Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday, Geronimo, Sitting Bull, Billy the Kid, Wild Bill Hickok, Annie Oakley, Kit Carson, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Matt Dillon. His name is associated with fabled places: Dodge City, Boot Hill,

the O.K. Corral, and Tombstone. He achieved his particular fame, according to one biographer, Stuart Lake, as “the greatest gun-fighting marshall that the Old West knew.”

Lake, who interviewed Earp in his last years, summed him up as follows: “Wyatt Earp was a man of action. He was born, reared, and lived in an environment which held words and theories of small account, in which

sheer survival often, and eminence invariably, might be achieved through deeds alone. Withal, Wyatt Earp was a thinking man, whose mental processes were as quick, as direct, as unflustered by circumstance and as effective as the actions they inspired.”

A less exalted image of Wyatt Earp emerges from the scrutiny of Frank Waters, a veteran observer of American Southwest landscape and history. “Wyatt,” he wrote, “was an itinerant saloonkeeper, cardsharp, gunman, bigamist, church deacon, policeman, bunco artist, and a supreme confidence man. A lifelong exhibitionist ridiculed alike by members of his own family, neighbors, contemporaries, and the public press, he lived his last years in poverty, still mainly trying to find someone to publicize his life, and died two years before his fictitious biography recast him in the role of America’s most famous frontier marshal.”

Differing Views of Wyatt Earp

The truth, as is common enough with historical figures about whom we know more from oral tradition than from documentation, undoubtedly lies between these extremes. The lives of those who became legend in the history of the West are perhaps even more embellished, for good or ill, as a result of sensational exaggeration by journalists and other writers. Confrontations between cowboys and Indians in the American “wild West” have long fascinated foreign audiences.

British writers accompanied William F. (“Buffalo Bill”) Cody on his expeditions, for example, producing “penny dreadfuls,” cheap, paperbound books that sensationalized the wanton killing of Indians and of buffalo. Clint Eastwood’s celebrated “anti-western,” Unforgiven, includes a writer who takes notes throughout on the mayhem. Eastwood’s earlier westerns were produced in Italy; the Japanese, in their films, found parallels between itinerant, free-lance gunslingers and early samurai warriors. The raw, physical energies that supposedly characterized western pioneers fascinate French intellectuals.

Nevertheless, the mere facts about the Earp family offer an unchallenged, epical account of the turbulent,

confused, sometimes noble, sometimes less than savory or honorable development and exploitation of America’s western frontiers in the decades after the Civil War. To establish their hold on the variegated

landscape, settlers had to contend with extravagantly hard seasons and the hostility of natives who were being callously displaced.

Wyatt Earp & The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

In 1879, Earp and his longtime companion, the former prostitute Mattie Blaylock, left Dodge City for Tombstone, Arizona. The town was booming after a silver rush, and most of the Earp family had gathered there. Virgil was working as the town marshal, and Wyatt began working alongside him. In March 1881, while pursuing a group of cowboys who had robbed a stagecoach, Wyatt struck a deal with local rancher Ike Clanton, who had ties to the cowboys. Clanton soon turned against him, however, and began threatening the Earp brothers. The feud escalated, and finally exploded into violence on October 26, 1881 at the O.K. Corral.

Earp was the last surviving participant of the OK Corral shootout.

Earp died at his home in Los Angeles, possibly of chronic cystitis, on January 13, 1929, at age 80. His longtime companion Josephine (she called herself Josephine Earp, although there’s no record they ever were

married) had his cremated remains buried at a cemetery in Colma, California. Earp, who had no children, was the last surviving participant of the OK Corral gunfight. In his later years, he’d consulted on Hollywood westerns and gotten to known various actors and directors. His funeral was attended by such celebrities as

Western film star Tom Mix, who served as a pallbearer.

After his death, Earp was portrayed by Hollywood as a heroic lawman, thanks in part to a best-selling—but

significantly embellished—1931 biography, “Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshall” by Stuart Lake. The book helped spawn movies and TV series about Earp, starring actors from Henry Fonda to James Garner to Kevin Costner in the lead role.

In the gunfight, Virgil, Morgan and Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday faced off against the Clanton gang (Ike, his brother Billy, and Tom and Frank McLaury). Morgan, Virgil and Holliday were all wounded, but survived; Billy and the McLaurys were killed; and Wyatt Earp escaped without injury. Ike Clanton filed murder charges against the Earp brothers and Holliday, but a judge cleared them in late November. On a hunt for the culprits, Wyatt and his gang killed

several suspects, then decided to leave town to avoid prosecution.

Final Years and Death

On Jan. 13, 1929, Wyatt Earp died in Los Angeles at the age of 80. moreover,Cowboy actors Tom Mix and William S. Hart were among his pallbearers. Wyatt’s cremated ashes were buried in Josie’s family plot in Colma,

California, just south of San Francisco. When Josie died at the age of 75, she was buried there beside him.

Earp’s enduring legacies include his role in shaping the West as a frontiersman, a lawman, a gambler and a prospector. A post office near his Mojave Desert mining claims along the Colorado River on Route 62 bears

his name — “Earp, California 92242”.

On a recent trip to Earp, California,

DesertUSA staff was accompanied by Ken Cilch, author of the book, “Wyatt Earp: The Missing Years.” With Ken’s help we found one of Wyatt’s old mining claims, some rusty old nails and some interesting rocks. We also visited the Earp Post Office, which had many pictures and displays of Wyatt Earp.

MORE POSTS: