formerly held by portugal spain and brazil

Hello dear friends, thanks for choosing us. In this post on the solsarin site, we will talk about “formerly held by portugal spain and brazil”.

Stay with us.

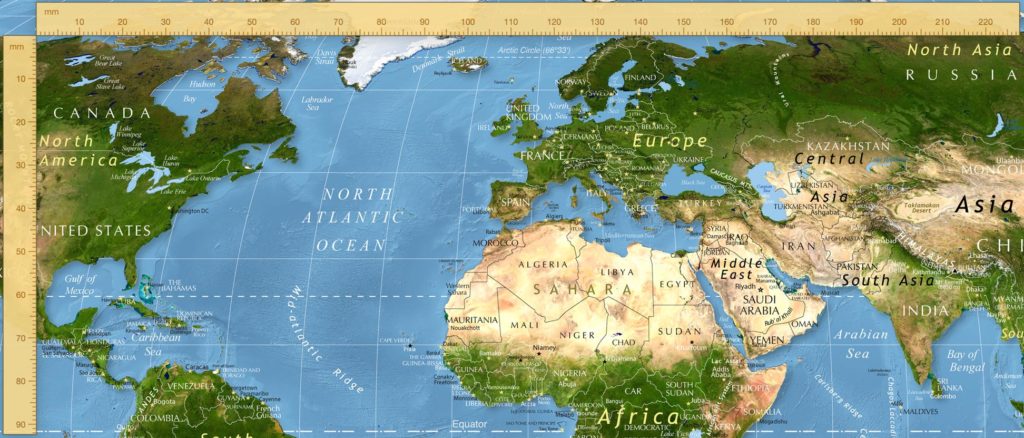

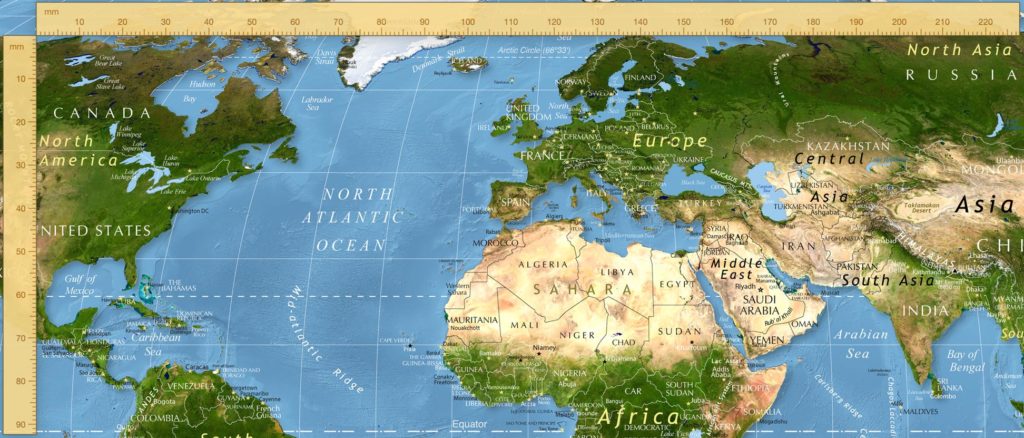

What country is formerly held by Portugal Spain and Brazil?

The South American country of Uruguay has the distinction of being a possession of Portugal, Spain and Brazil. The region of Uruguay was first explored by Portuguese explorers in 1512-1513. Spanish explorers would arrive soon afterwards in 1516. The Spanish and Portuguese would clash over the area until it gained independence from Spain in 1814. In 1821 it was invaded by the Portuguese and annex as part of Brazil. Once Brazil split off from Portugal, Uruguay went with it and was part of the Brazilian Empire until 1828 when it re-gained its independence.

The independence of Latin America

After three centuries of colonial rule, independence came rather suddenly to most of Spanish and Portuguese America. Between 1808 and 1826 all of Latin America except the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico slipped out of the hands of the Iberian powers who had ruled the region since the conquest. The rapidity and timing of that dramatic change were the result of a combination of long-building tensions in colonial rule and a series of external events.

The reforms imposed by the Spanish Bourbons in the 18th century provoked great instability in the relations between the rulers and their colonial subjects in the Americas. Many Creoles (those of Spanish parentage but who were born in America) felt Bourbon policy to be an unfair attack on their wealth, political power, and social status. Others did not suffer during the second half of the 18th century; indeed, the gradual loosening of trade restrictions actually benefited some Creoles in Venezuela and certain areas that had moved from the periphery to the centre during the late colonial era. However, those profits merely whetted those Creoles’ appetites for greater free trade than the Bourbons were willing to grant. More generally, Creoles reacted angrily against the crown’s preference for peninsulars in administrative positions and its declining support of the caste system and the Creoles’ privileged status within it. After hundreds of years of proven service to Spain, the American-born elites felt that the Bourbons were now treating them like a recently conquered nation.

In cities throughout the region, Creole frustrations increasingly found expression in ideas derived from the Enlightenment. Imperial prohibitions proved unable to stop the flow of potentially subversive English, French, and North American works into the colonies of Latin America. Creole participants in conspiracies against Portugal and Spain at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century showed familiarity with such European Enlightenment thinkers as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Montesquieu, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The Enlightenment clearly informed the aims of dissident Creoles and inspired some of the later, great leaders of the independence movements across Latin America.

MORE POSTS FOR YOU:

- does fedex deliver on saturday

- koala marsupial

- how much alcohol in budweiser select

- elephant trunk snake lifespan

- what percent alcohol is jameson whiskey

Buenos Aires achieved similarly mixed results in other neighbouring regions, losing control of many while spreading independence from Spain. Paraguay resisted Buenos Aires’ military and set out on a path of relative isolation from the outside world. Other expeditions took the cause to Upper Peru, the region that would become Bolivia. After initial victories there, the forces from Buenos Aires retreated, leaving the battle in the hands of local Creole, mestizo, and Indian guerrillas. By the time Bolívar’s armies finally completed the liberation of Upper Peru (then renamed in the Liberator’s honour), the region had long since separated itself from Buenos Aires.

The main thrust of the southern independence forces met much greater success on the Pacific coast. In 1817 San Martín, a Latin American-born former officer in the Spanish military, directed 5,000 men in a dramatic crossing of the Andes and struck at a point in Chile where loyalist forces had not expected an invasion. In alliance with Chilean patriots under the command of Bernardo O’Higgins, San Martín’s army restored independence to a region whose highly factionalized junta had been defeated by royalists in 1814. With Chile as his base, San Martín then faced the task of freeing the Spanish stronghold of Peru. After establishing naval dominance in the region, the southern movement made its way northward. Its task, however, was formidable. Having benefited from colonial monopolies and fearful of the kind of social violence that the late 18th-century revolt had threatened, many Peruvian Creoles were not anxious to break with Spain. Consequently, the forces under San Martín managed only a shaky hold on Lima and the coast. Final destruction of loyalist resistance in the highlands required the entrance of northern armies.

The north and the culmination of independence

Independence movements in the northern regions of Spanish South America had an inauspicious beginning in 1806. The small group of foreign volunteers that the Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda brought to his homeland failed to incite the populace to rise against Spanish rule. Creoles in the region wanted an expansion of the free trade that was benefiting their plantation economy. At the same time, however, they feared that the removal of Spanish control might bring about a revolution that would destroy their own power.

Brazil

Brazil gained its independence with little of the violence that marked similar transitions in Spanish America. Conspiracies against Portuguese rule during 1788–98 showed that some groups in Brazil had already been contemplating the idea of independence in the late 18th century. Moreover, the Pombaline reforms of the second half of the 18th century, Portugal’s attempt to overhaul the administration of its overseas possessions, were an inconvenience to many in the colony. Still, the impulse toward independence was less powerful in Brazil than in Spanish America. Portugal, with more limited financial, human, and military resources than Spain, had never ruled its American subjects with as heavy a hand as its Iberian neighbour. Portugal neither enforced commercial monopolies as strictly nor excluded the American-born from high administrative positions as widely as did Spain. Many Brazilian-born and Portuguese elites had received the same education, especially at the University of Coimbra in Portugal. Their economic interests also tended to overlap. The reliance of the Brazilian upper classes on African slavery, finally, favoured their continued ties to Portugal. Plantation owners depended on the African slave trade, which Portugal controlled, to provide workers for the colony’s main economic activities. The size of the resulting slave population—approximately half the total Brazilian population in 1800—also meant that Creoles shied away from political initiatives that might mean a loss of control over their social inferiors.

The key step in the relatively bloodless end of colonial rule in Brazil was the transfer of the Portuguese court from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro in 1808. The arrival of the court transformed Brazil in ways that made its return to colony status impossible. The unprecedented concentration of economic and administrative power in Rio de Janeiro brought a new integration to Brazil. The emergence of that capital as a large and increasingly sophisticated urban centre also expanded markets for Brazilian manufactures and other goods. Even more important to the development of manufacturing in Brazil was one of the first acts undertaken there by the Portuguese ruler, Prince Regent John: the removal of old restrictions on manufacturing. Another of his enactments, the opening of Brazilian ports to direct trade with friendly countries, was less helpful to local manufacturers, but it further contributed to Brazil’s emergence as a metropolis.

Brazil headed into a political crisis when groups in Portugal tried to reverse the metropolitanization of their former colony. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars came calls for John to return to Lisbon. At first he demurred and in 1815 even raised Brazil to the status of kingdom, legally equal to Portugal within the empire that he ruled. The situation was a difficult one for John (after 1816 King John VI). If he moved back to Lisbon, he might lose Brazil, but if he remained in Rio, he might well lose Portugal. Finally, after liberal revolts in Lisbon and Oporto in 1820, the Portuguese demands became too strong for him to resist. In a move that ultimately facilitated Brazil’s break with Portugal, John sailed for Lisbon in 1821 but left his son Dom Pedro behind as prince regent. It was Dom Pedro who, at the urging of local elites, oversaw the final emergence of an independent Brazil.

Matters were pushed toward that end by Portuguese reaction against the rising power of their former colony. Although the government constituted by the liberals after 1820 allowed Brazilian representation in a Cortes, it was clear that Portugal now wanted to reduce Brazil to its previous colonial condition, endangering all the concessions and powers the Brazilian elite had won. By late 1821 the situation was becoming unbearable. The Cortes now demanded that Dom Pedro return to Portugal. As his father had advised him to do, the prince instead declared his intention to stay in Brazil in a speech known as the “Fico” (“I am staying”). When Pedro proclaimed its independence on Sept. 7, 1822, and subsequently became its first emperor, Brazil’s progression from Portuguese colony to autonomous country was complete. There was some armed resistance from Portuguese garrisons in Brazil, but the struggle was brief.

Independence still did not come without a price. Over the next 25 years Brazil suffered a series of regional revolts, some lasting as long as a decade and costing tens of thousands of lives. Dom Pedro I was forced from his throne in 1831, to be succeeded by his son, Dom Pedro II. The break with Portugal did not itself, however, produce the kind of disruption and devastation that plagued much of the former Spanish America. With its territory and economy largely intact, its government headed by a prince of the traditional royal family, and its society little changed, Brazil enjoyed continuities that made it extraordinarily stable in comparison with most of the other new states in the region.