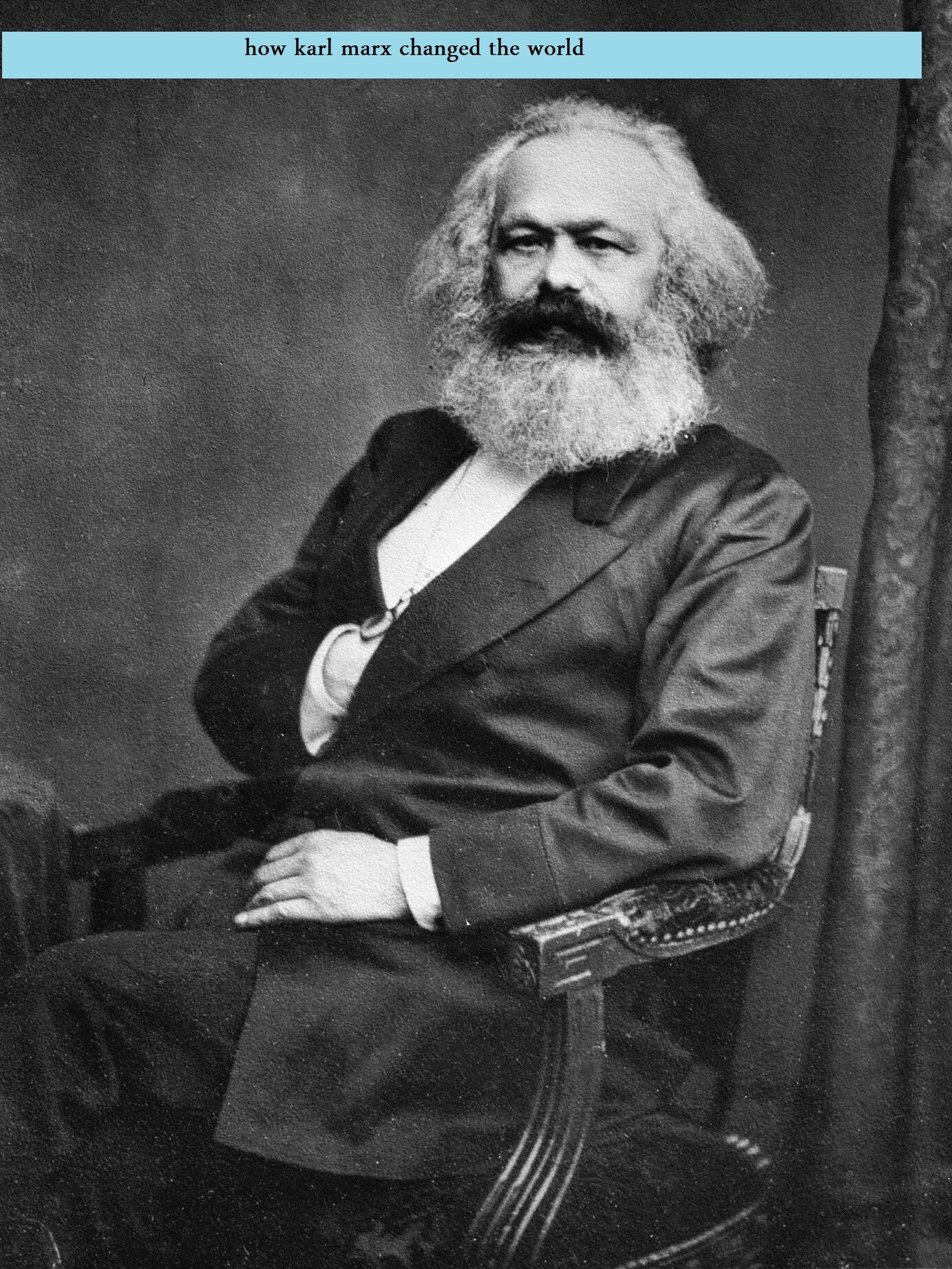

how karl marx changed the world

Hello dear friends, thank you for choosing us. In this post on the solsarin site, we will talk about ” how karl marx changed the world”.

Stay with us.

Thank you for your choice.

how karl marx died

Death

Following the death of his wife Jenny in December 1881, Marx developed a catarrh that kept him in ill health for the last 15 months of his life. It eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him in London on 14 March 1883, when he died a stateless person at age 64.[205] Family and friends in London buried his body in Highgate Cemetery.

how karl marx influence the world

One of the most important contributions of Karl Marx is his theory of historical materialism. … Marx identified six successive stages of the development of these material conditions in Western Europe: primitive communism; slave society; feudalism; capitalism; socialism; and communism.

how karl marx contribution to sociology

how karl marx contribution made an effect

how karl marx interpreted human history

Marx famously stated: ”The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. ” In other words, Marx believed that class struggle was the driving force in the flow of history. Thus, economics, not religion or ideology, was the decisive force turning the ”wheels” of historical development.

how karl marx analysis social change

what karl marx contribution to sociology

who’s karl marx sociology

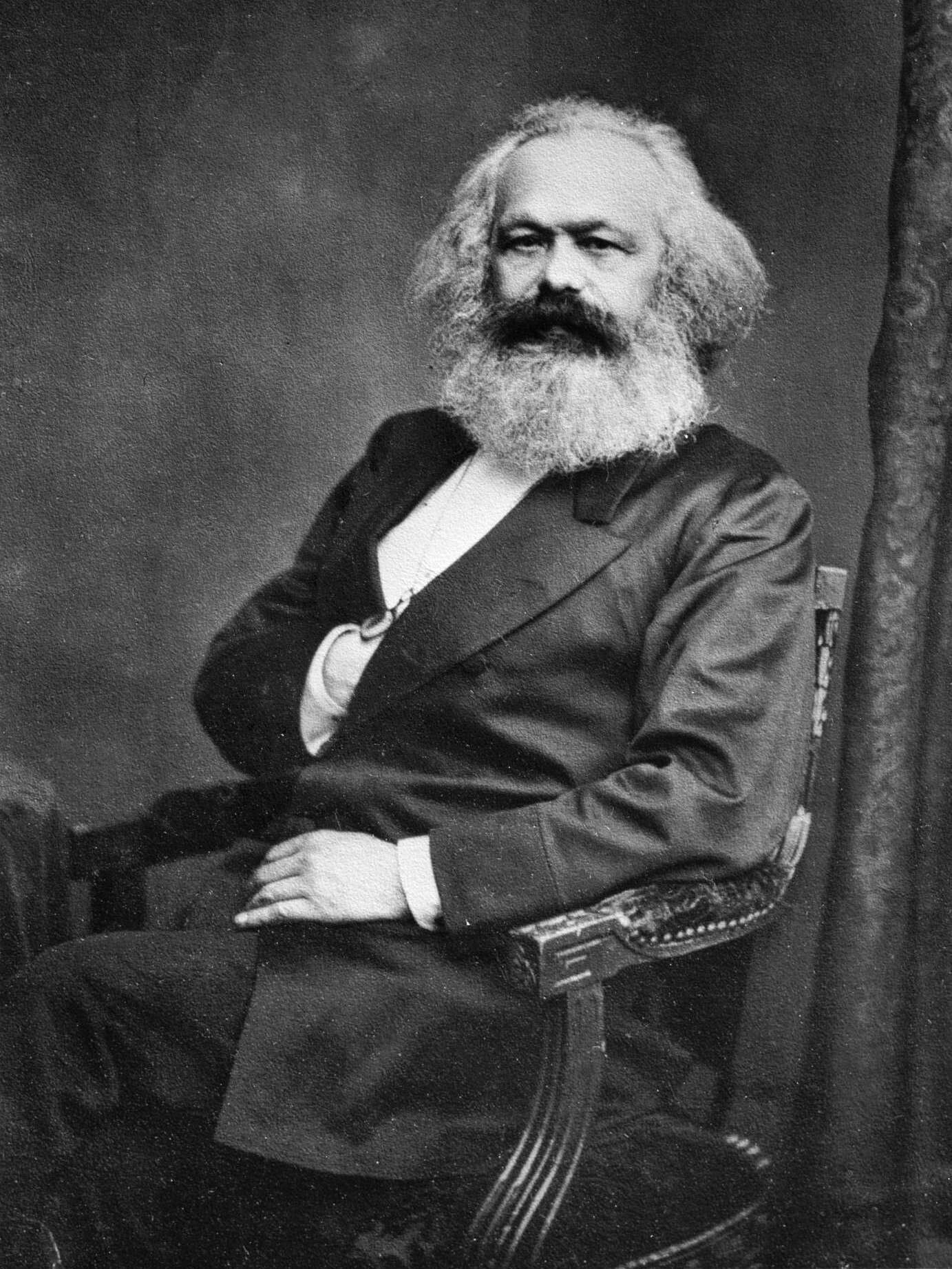

Karl Marx, Yesterday and Today

On or about February 24, 1848, a twenty-three-page pamphlet was published in London. Modern industry, it proclaimed, had revolutionized the world. It surpassed, in its accomplishments, all the great civilizations of the past—the Egyptian pyramids, the Roman aqueducts, the Gothic cathedrals. Its innovations—the railroad, the steamship, the telegraph—had unleashed fantastic productive forces. In the name of free trade, it had knocked down national boundaries, lowered prices, made the planet interdependent and cosmopolitan. Goods and ideas now circulated everywhere.How useful is Karl Marx—who died a hundred and thirty-three years ago—for understanding our world?Illustration by Roberto De Vicq De Cumptich

Just as important, it swept away all the old hierarchies and mystifications. People no longer believed that ancestry or religion determined their status in life. Everyone was the same as everyone else. For the first time in history, men and women could see, without illusions, where they stood in their relations with others.

The new modes of production

The new modes of production, communication, and distribution had also created enormous wealth. But there was a problem. The wealth was not equally distributed. Ten per cent of the population possessed virtually all of the property; the other ninety per cent owned nothing. As cities and towns industrialized, as wealth became more concentrated, and as the rich got richer, the middle class began sinking to the level of the working class.

Soon, in fact, there would be just two types of people in the world: the people who owned property and the people who sold their labor to them.

As ideologies disappeared which had once made inequality appear natural and ordained, it was inevitable that workers everywhere would see the system for what it was, and would rise up and overthrow it. The writer who made this prediction was, of course, Karl Marx, and the pamphlet was “The Communist Manifesto.” He is not wrong yet.

contemporary politics

Considering his rather glaring relevance to contemporary politics, it’s striking that two important recent books about Marx are committed to returning him to his own century. “Marx was not our contemporary,” Jonathan Sperber insists, in “Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life” (Liveright), which came out in 2013; he is “more a figure of the past than a prophet of the present.”

And Gareth Stedman Jones explains that the aim of his new book, “Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion” (Harvard), is “to put Marx back in his nineteenth-century surroundings.”

The mission is worthy. Historicizing—correcting for the tendency to presentize the past—is what scholars do. Sperber, who teaches at the University of Missouri, and Stedman Jones, who teaches at Queen Mary University of London and co-directs the Centre for History and Economics at the University of Cambridge.

both bring exceptional learning to the business of rooting Marx in the intellectual and political life of nineteenth-century Europe.

Marx

Marx was one of the great infighters of all time, and a lot of his writing was topical and ad hominem—no-holds-barred disputes with thinkers now obscure and intricate interpretations of events largely forgotten. Sperber and Stedman Jones both show that if you read Marx in that context, as a man engaged in endless internecine political and philosophical warfare, then the import of some familiar passages in his writings can shrink a little. The stakes seem more parochial. In the end, their Marx isn’t radically different from the received Marx, but he is more Victorian. Interestingly, given the similarity of their approaches, there is not much overlap.

Still, Marx was also what Michel Foucault called the founder of a discourse. An enormous body of thought is named after him. “I am not a Marxist,” Marx is said to have said, and it’s appropriate to distinguish what he intended from the uses other people made of his writings.

But a lot of the significance of the work lies in its downstream effects. However he managed it, and despite the fact that, as Sperber and Stedman Jones demonstrate, he can look, on some level, like just one more nineteenth-century system-builder who was convinced he knew how it was all going to turn out, Marx produced works that retained their intellectual firepower over time. Even today, “The Communist Manifesto” is like a bomb about to go off in your hands.