How were the Okies treated in California?

Hello everyone. Welcome to solsarin. This amazing text is about “How were the Okies treated in California?”. If you are interested in this topic, stay with us and share it to your friends.

Okie

An Okie is a person identified with the state of Oklahoma. This connection may be residential, ethnic, historical or cultural. For most Okies, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being Oklahoman.

In California, the term came to refer to very poor migrants from Oklahoma coming to look for employment. The Dust Bowl and the “Okie” migration of the 1930s brought in over a million climate migrants, many headed to the farm labor jobs in the Central Valley. By 1950, four million individuals, or one quarter of all persons born in Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, or Missouri, lived outside the region, primarily in the West.

Prominent Okies included singer/songwriter Woody Guthrie and country musician Merle Haggard. John Steinbeck wrote about Okies moving west in his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath, which was filmed in 1940 by John Ford.

Great Depression usage

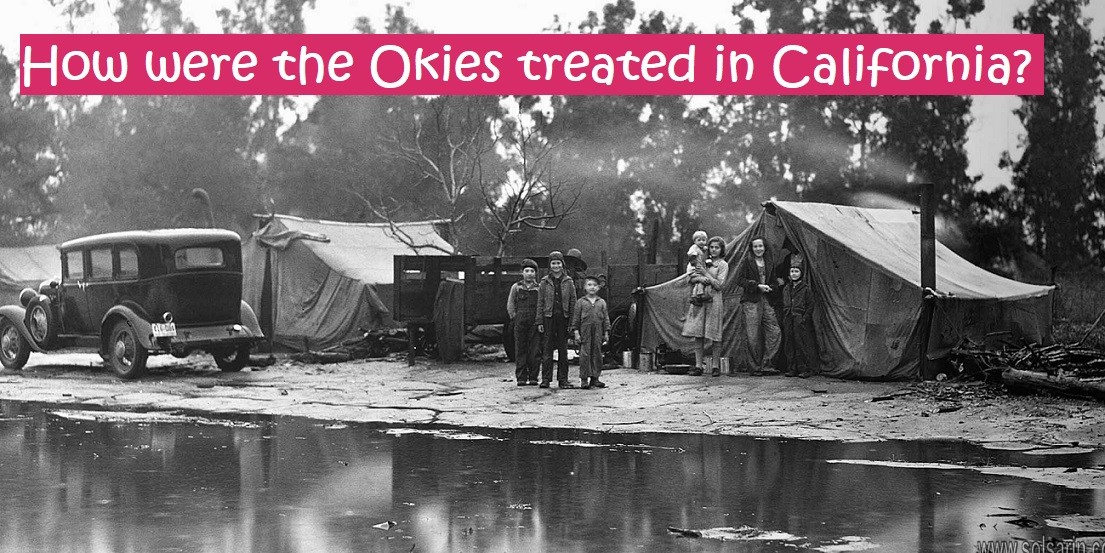

In the mid-1930s, during the Dust Bowl era, large numbers of farmers fleeing ecological disaster and the Great Depression migrated from the Great Plains and Southwest regions to California mostly along historic U.S. Route 66. Californians began calling all migrants by that name, even though many newcomers were not actually Oklahomans.

The migrants included people from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, Colorado and New Mexico, but were all referred to as “Okies” and “Arkies”. More of the migrants were from Oklahoma than any other state, and a total of 15% of the Oklahoma population left for California.

Ben Reddick; a free-lance journalist and later publisher of the Paso Robles Daily Press; is credited with first using the term Oakie; in the mid-1930s, to identify migrant farm workers. He noticed the “OK” abbreviation (for Oklahoma) on many of the migrants’ license plates and referred to them in his article as “Oakies”. The first known usage was an unpublished private postcard from 1907.

The Great Okie Migration

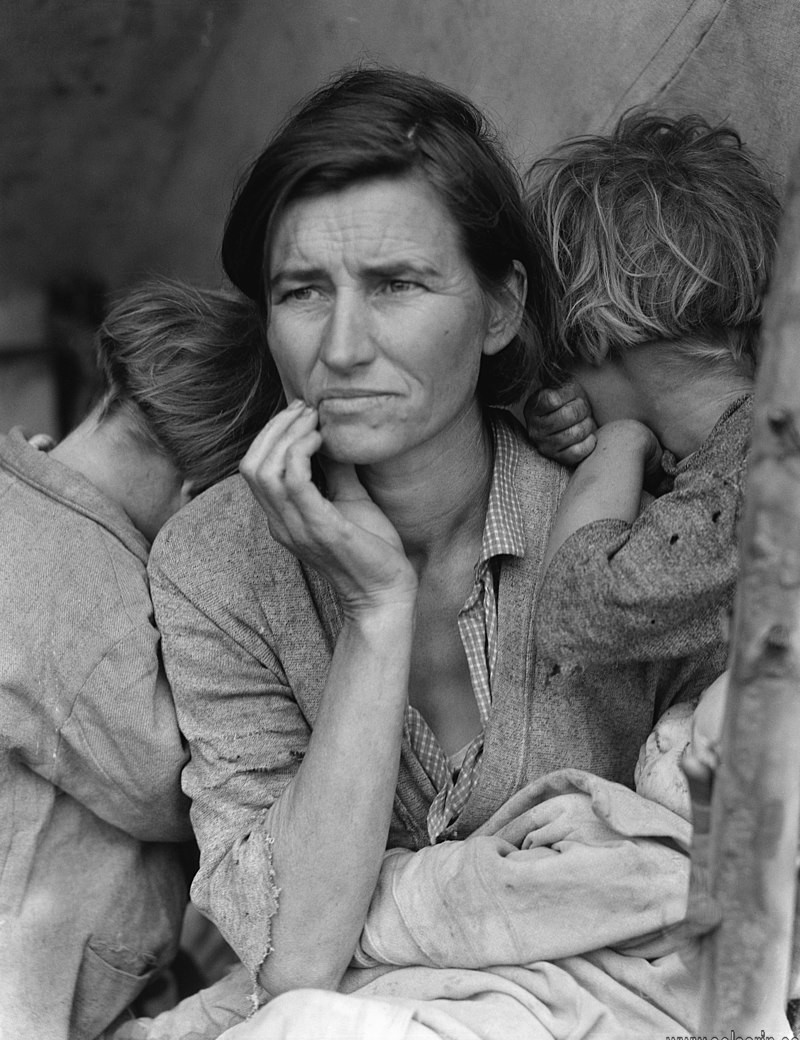

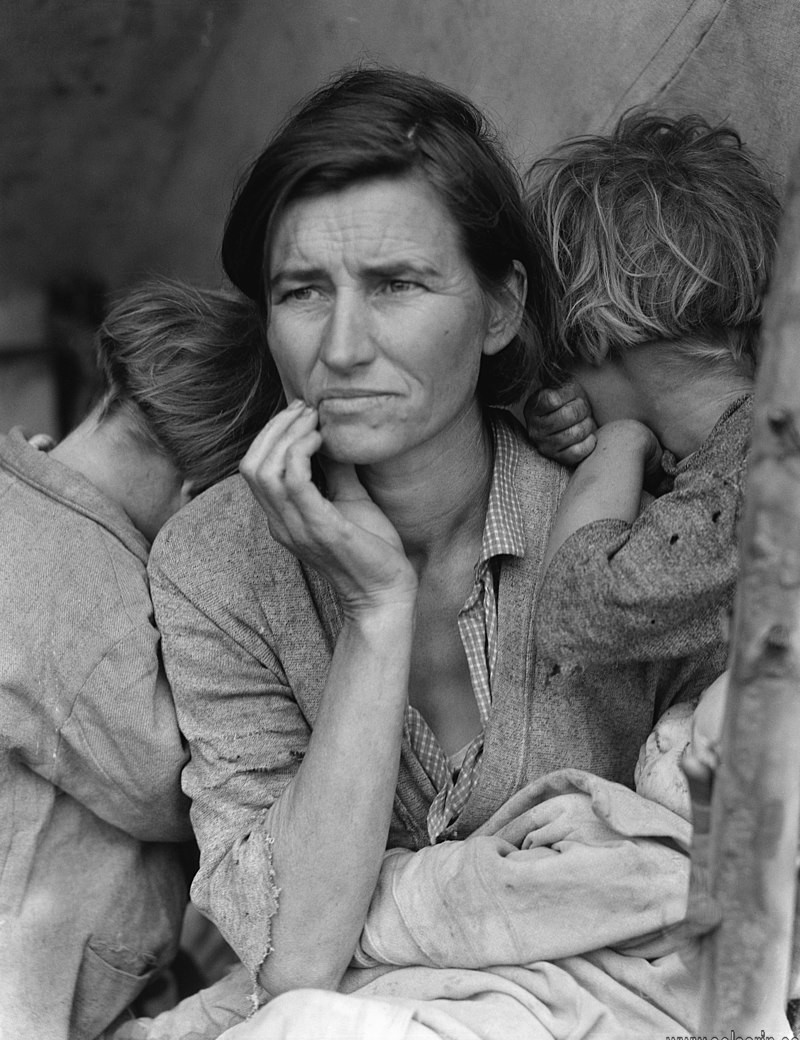

The impact of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl on rural Americans was substantial. The damaging environmental effects of the dust storms had not only dried up the land, but it had also dried up jobs and the economy. The drought caused a cessation of agricultural production, leading to less income for farmers, and consequently less food on the table for their families.

The increased mechanization of farming began to consolidate smaller farms into large farms. Many farmers lost their land in bank foreclosures. Poverty became rampant. In his fictionalized autobiography, American folk singer Woody Guthrie commented on the dire straits:

“They was hundreds and hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of thousands of families of people living around under railroad bridges, down along the river bottoms, and in old cardboard houses, and in old, rusty beat-up houses that they’d made up out of tote sacks and old dirty rags and corrugated iron that they got out of the dumps and old tin cans flattened out, and old orange crates.”

The survival of their families at stake, these Okies faced a difficult decision – stay on their land in the hopes that the drought would end, or leave in search of more fertile land with plentiful job opportunities. Tens of thousands of displaced and destitute people, dubbed Dust Bowl refugees by the press, journeyed west to California in search of farm labor jobs, in an event nicknamed the Okie Migration.

These migrants came from a broad swath of southern plains states including Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas. The two artworks featured here, Dust Bowl and Valley Farms, represent the journey migrants took from the Dust Bowl states to the fertile farmland of California.

Okies and the Politics of Plain-Folk Americanism

Native Sons

If the debasement of California’s nonwhites had therapeutic and group definitional implications, the migrants’ concept of Americanism figured more ambiguously in relations with the state’s whites, most of whom possessed old-stock credentials not much different than their own. Mostly, Americanism provided a bridge. That so many of the Californians were “Americans” minimized the migrants’ defensive reactions and sustained their interest in assimilation, which as we have seen was one compelling strategy of adjustment.

But for some members of the group, expectations about the behavior of proper Americans also provided ammunition for criticizing their native hosts. And while this endeavor was but a weak reflection of the disdain Okies knew was directed their own way, it offered some measure of emotional conciliation and group definition.

Southwesterners used several devices to turn the tables on Californians, the simplest of which were snide labels of their own, including “Calies,” “native sons,” and the curious favorite, “prune pickers,” which played on the bathroom humor associated with the sticky, sweet dried fruit. A stereotype accompanied the labels, the thrust of which was that Californians were selfish, arrogant, “privileged characters” who thought they were better than everyone else. As one novice poet put it:

Some of the Californians go around, with their nose stuck up;

Like when it would rain, They’d use it for a cup.

This view of rude and haughty natives was often coupled with the notion that Californians had grown soft and lazy, and furthermore that their resentment of the migrants was rooted in jealousy and fear. “If it weren’t for Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas, there wouldn’t be much to California, would there?” a migrant hitchhiker lectured Charles Todd. He figured that everybody else in the state had forgotten the meaning of real work.

As have-nots often do, the migrants also enjoyed suggestions that Californians’ lofty social positions rested upon lowly origins and ill-gotten or unearned wealth. A popular ditty that apparently pre-dated the Dust Bowl migration delighted Okies with its irreverent view of the California pedigree.

The miners came in forty-nine,

The whores in fifty-one;

And when they bunked together

They begot the native son.

The author of a letter to the Modesto Bee had different suspicions about California bloodlines. Establishing his own credentials as a “native son of the U.S.A.” whose “father and grandfather served in the Civil War,” he addressed his challenge “to the native son who owns your big dairies, your big vineyards, your big orchards, look up the records and get the facts. . . .

The few I have worked for, I have been informed, got their starts from their fathers, who happened not to be native sons.” Here was the plain folks’ critique in a nutshell: “big” farms, too big and too cushy; unearned wealth and social position; and possibly immigrant backgrounds. It was quite a brief.

Still, these attempts at denigration, unlike those directed at nonwhites, were not particularly serious. Few Okies really entertained feelings of superiority over white Californians. Most of the jibes were simply attempts to reassure themselves and regain some composure.

Nevertheless, the process had bearing on the emerging subculture. In clarifying their definitions of proper Americanism and in laying special claim to that heritage, the migrants were developing an identity capable of sustaining a group experience that initially owed its existence to external forces of class and prejudice.

We will let Ernest Martin restate the proposition that underlay the group identity. An Oklahoman who came to California as a child, grew up in the valley, then moved to Los Angeles and became a minister and religious scholar, he speaks boldly and with insight about the cultural and cognitive parameters of the Okie experience. They considered themselves “the best Americans in the world,” he recalls. “To our people their way of life was America. New York isn’t America . . . we were America.”

There is no simple statement of regional pride. The Okie subculture was anchored in a group concept that is not reducible to the ethnic formula that scholars sometimes employ in relation to other groups of Southern white out-migrants. Instead of a particularistic definition of the group based on state origins, many Southwesterners laid claim to a nativist conception of national community.

Plain-folk Americanism was in some respects a regional enterprise—white Southerners were its core proponents in California—but it also spoke to and for whites of many other backgrounds. Hence, the curious dynamics of the Okie subculture.

Southwesterners drew together and gained feelings of pride and definition from this ideological system but never manifested the exclusivity, the insularity, of an ethnic subsociety. Plain-folk Americanism gave their community a different thrust, outward and expansive, open to other whites who embraced the proper values. These heartlanders had come to California with something not just to save but to share.

This would become increasingly clear in the decades to come. The 1940s would simultaneously reduce the structures of social and economic isolation and encourage the proliferation of key cultural institutions. Country music and evangelical churches would become important emblems of the

Okie group in the post-Depression decades. And each would function in the dual manner we have been observing, on the one hand solidifying elements of group pride, while also carrying messages of wider appeal that helped to spread the Okie cultural impact far beyond the formal boundaries of the Southwestern group.