The stability of personality traits is best illustrated by the consistency of

Hey guys! We return with an amazing topic aboutThe stability of personality traits . This is “The stability of personality traits is best illustrated by the consistency of”. As always, read the text, share it to your friends and comment us in solsarin.

Personality Stability

This is an edited and adapted chapter from Donnellan, M. B. (2019) in the NOBA series on psychology. For full attribution see end of chapter.

This module describes different ways to address questions about personality stability across the lifespan. Definitions of the major types of personality stability are provided, and evidence concerning the different kinds of stability and change are reviewed. The mechanisms thought to produce personality stability and personality change are identified and explained.

Personality trait stability

Personality stability is an interesting and ongoing researched topic.

For the most part, personality traits are remarkably stable and continue to persist relatively nonfluctuating and steady over time.

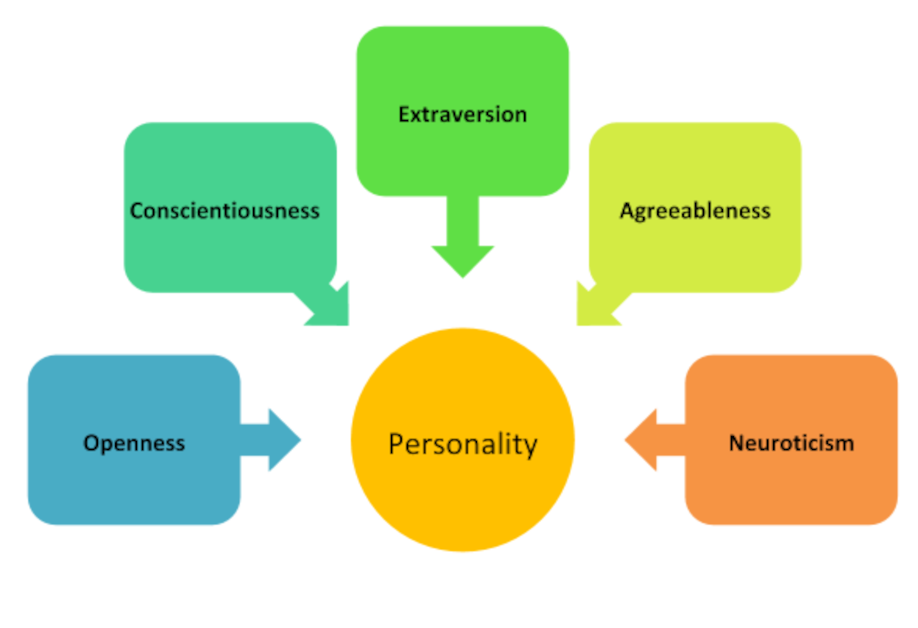

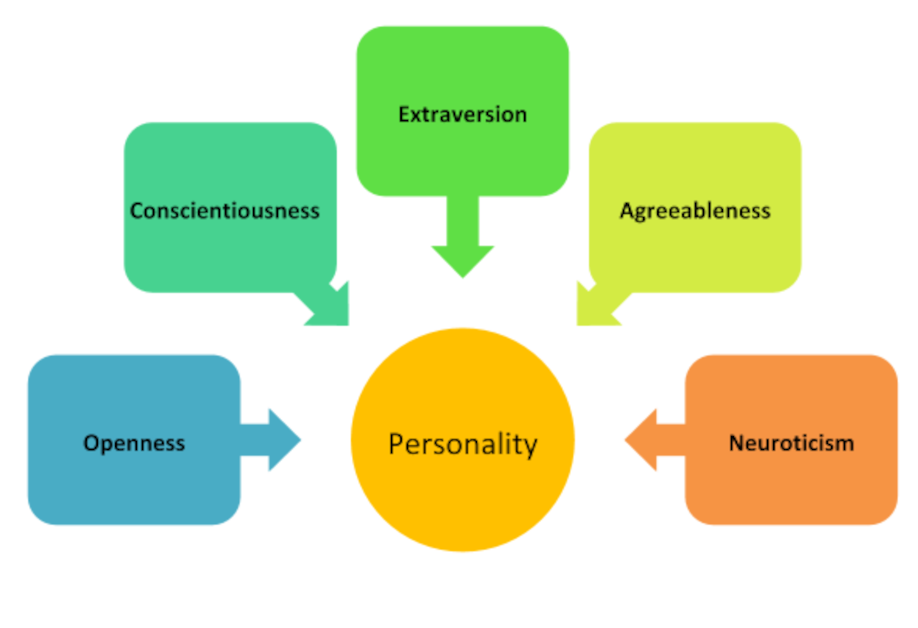

The stability of personality traits is best illustrated by the consistency of the Big Five personality traits throughout one’s life.

But that doesn’t mean that personality traits stop developing. As a matter of fact, personality continues to develop in all age groups, including old age.

Human personality shows the greatest stability during late adulthood and tend to fluctuate more during childhood. This can be explained due to the rapidly occurring changes in one’s evolving brain and, thus, also the neurochemistry that influences and shapes our behavior.

Furthermore, personality traits tend to fluctuate more in old age compared to adulthood due to changes in social demands and life experiences. This means that personality stability is less in old age compared to adulthood.

However, the Big 5 personality traits extraversion and conscientiousness tend to increase the most with age, while openness and agreeableness tend to increase as well, but to a lesser degree.

Personality trait neuroticism tends to decrease with age, possibly due to becoming more self-confident and due to developing more and improved coping mechanisms.

Let’s explore what the current research has to say about personality trait stability.

Facets of Traits (Subtraits)

So how does it feel to be told that your entire personality can be summarized with scores on just five personality traits? Do you think these five scores capture the complexity of your own and others’ characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors?

Most people would probably say no, pointing to some exception in their behavior that goes against the general pattern that others might see. For instance, you may know people who are warm and friendly and find it easy to talk with strangers at a party yet are terrified if they have to perform in front of others or speak to large groups of people.

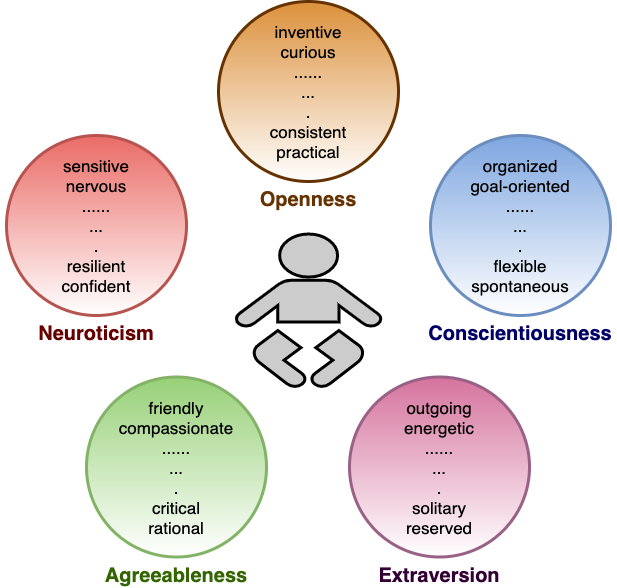

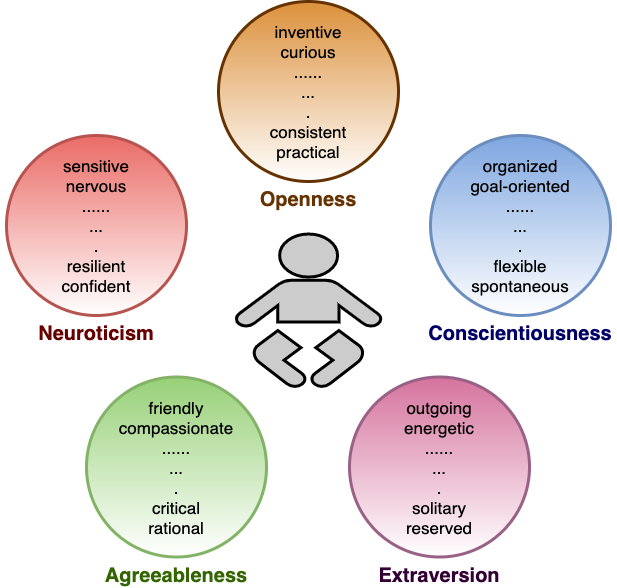

The fact that there are different ways of being extraverted or conscientious shows that there is value in considering lower-level units of personality that are more specific than the Big Five traits. These more specific, lower-level units of personality are often called facets.

To give you a sense of what these narrow units are like, Figure 4 shows facets for each of the Big Five traits. It is important to note that although personality researchers generally agree about the value of the Big Five traits as a way to summarize one’s personality, there is no widely accepted list of facets that should be studied. The list seen here, based on work by researchers Paul Costa and Jeff McCrae, thus reflects just one possible list among many. It should, however, give you an idea of some of the facets making up each of the Five-Factor Model.

Facets can be useful because they provide more specific descriptions of what a person is like. For instance, if we take our friend who loves parties but hates public speaking, we might say that this person scores high on the “gregariousness” and “warmth” facets of extraversion, while scoring lower on facets such as “assertiveness” or “excitement-seeking.”

This precise profile of facet scores not only provides a better description, it might also allow us to better predict how this friend will do in a variety of different jobs (for example, jobs that require public speaking versus jobs that involve one-on-one interactions with customers).

Because different facets within a broad, global trait like extraversion tend to go together (those who are gregarious are often but not always assertive), the broad trait often provides a useful summary of what a person is like. But when we really want to know a person, facet scores add to our knowledge in important ways.

The stability of personality traits in individuals with borderline personality disorder

Although stability and pervasive inflexibility are general criteria for DSM-IV personality disorders (PD), borderline PD (BPD) is characterized by instability in several domains including interpersonal behavior, affect, and identity. We hypothesized that such inconsistencies notable in BPD may relate to instability at the level of the basic personality traits that are associated with this disorder.

Five types of personality trait stability across 4 assessments over 6 years were compared for BPD patients (N = 130 at first interval) and patients with other PDs (N = 302). Structural stability did not differ across groups. Differential stability tended to be lower for Five Factor Model traits in the BPD group, with the strongest and most consistent effects observed for neuroticism and conscientiousness.

Growth curve models suggested that these two traits also showed greater mean-level change, with neuroticism declining faster and conscientiousness increasing faster, in the BPD group. The BPD group was further characterized by greater individual-level instability for neuroticism and conscientiousness in these models.

Finally, the BPD group was less stable in terms of the ipsative configuration of FFM facet-level profiles than was the other PD group over time. Results point to the importance of personality trait instability in characterizing BPD.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

The sample was composed of 371 secondary education students whose mean age was 12.03 years (SD = 0.60) and who answered the personality scales in 2004 (Time 1, T1). Of these, 234 (90 boys and 144 girls; mean age = 15.32, SD = 0.71) were re-assessed 3 years later in 2007 (Time 2, T2).

The attrition analysis indicated that the participants who answered at both T1 and T2 were moderately more agreeable, t(369) = 2.63, p = 0.009; and open to experience, t(369) = 2.48, p = 0.014, than those who answered only at T1. However, there were no significant differences in the percentage of male and female participants or in their parents’ socioeconomic status.

The participating students belonged to four high schools in the province of Castelló (east Spain). Four trained research assistants handed out the questionnaires, followed the standard instructions and encouraged respondents to give sincere answers. All the attending students voluntarily completed the questionnaires in the classroom and did not receive any compensation for their participation.

Ethics

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the ethical committee from the Universitat Jaume I. Parents or legal tutors of the participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

In this study we used a short form of the Junior Spanish NEO-PI-R, which comprises 150 items, answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. It assesses 30 specific traits or facets that define the five personality factors or domains: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

JS NEO-S can be used in adolescents aged 12–18 years. In the present study the Cronbach alphas for the five personality domains in T1 were: neuroticism = 0.79, extraversion = 0.75, openness = 0.65, agreeableness = 0.74, and conscientiousness = 0.86, while in T2 were: neuroticism = 0.88, extraversion = 0.84, openness = 0.81, agreeableness = 0.78, and conscientiousness = 0.91.

Results

Structural Consistency

We formally tested if intercorrelations among FFM dimensions changed from T1 to T2 using SEM. The base line model leads to a fully saturated model (CFI = 1.00). We reestimated the model after placing 10 pairwise equality constraints between paths at T1 and T2.

A chi-squared difference test indicated that constraining the model did not lead to a significant reduction in fit, χ2Δ (df = 10) = 11.58, p = 0.314; CFI = 0.99, indicating that the saturated model did not fit better than the model with equal correlations. Therefore, we can conclude that the intercorrelations of the Big Five were structurally invariant across the two measurement points.

In addition, we performed the Procrustes rotation and obtained the factor congruence coefficients for each dimension. Thus, structure at T1 and the structure at T2 were rotated toward the adult North American structure of the NEO-PI-R, and structure at T1 was rotated toward the structure at T2. According to congruence coefficients >0.85 are higher than 95% of the rotations from random data, and factor congruence near 0.90 can be considered clearly replicated.

When factor structures at T1 and T2 were compared to adult structure, the congruence coefficients were 0.85 and 0.86 for openness at T1 and T2, respectively, and ranged from 0.88 to 0.95 for the rest of traits. In addition, the congruence coefficients between T1 and T2 ranged between 0.90 and 0.94 for neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, but openness presented a coefficient of 0.85.

Accordingly, our data indicates that Spanish adolescent structure at T1 and T2 closely approximates the American adult structure, and that the structure at T1 was clearly replicated at T2, although openness presented some replicability problems.

Mean-Level Change

Table 2 presents the results of the mean comparisons made of the five personality dimensions between Times T1 and T2. The conscientiousness and, to a lesser extent, the agreeableness mean scores lowered, which may indicate a teenage rebellion pattern in this stage. No mean-level changes were found for neuroticism, extraversion, and openness.

Rank-Order Consistency

The correlation indices of each personality dimension between T1 and T2 were 0.42 for neuroticism, 0.47 for extraversion, 0.49 for openness, 0.50 for agreeableness, and 0.45 for conscientiousness. The five index correlations were significant at p < 0.001. Thus, our results indicate that personality is relatively stable in adolescence.

Individual Differences in Change

The RC indices of the five personality dimensions were computed. Lower percentages of participants were obtained for domains extraversion, openness, and agreeableness (fewer than 10%). Conversely, neuroticism (more than 20%) and conscientiousness (more than 30%) obtained the highest percentage of participants with significant RC indices.

Furthermore, extraversion and agreeableness showed a balanced percentage of participants with lower and higher values for the RC indices, but conscientiousness presented the largest difference (more than a 30% decrease and less than a 2% increase).

Ipsative Consistency

Cronbach’s and Gleser’s D2, D′2, D″2 indices of the five domains were calculated. The results indicated low percentages of change in the elevation (N = 10, 4.3%), scatter (N = 9, 3.9%), or shape (N = 14, 6%) of individual profiles. Only 9.8% of the participants exhibited change in any of these three indices.

The q-correlations were also computed and the results revealed that the average was 0.49 (ranging from −0.52 to 0.80) and the median was 0.58. The Q1and Q3of the q-correlations distribution were 0.36 and 0.71, respectively. The 77.3% of the participants obtained q-correlations of over 0.30 and 6.4% of the participants obtained negative values (r < 0).

Random Posts

- butternut squash ravioli sauce

- what type of planing hull handles rough water

- white chicken chili pioneer woman

- chicken drumstick recipes oven

- cream of mushroom chicken crockpot

- microwavable mac and cheese kraft

- pasta with chicken and sausage

- best potatoes for mashed potatoes

- why did piccolo turn good

- pioneer woman slow cooker chicken thighs