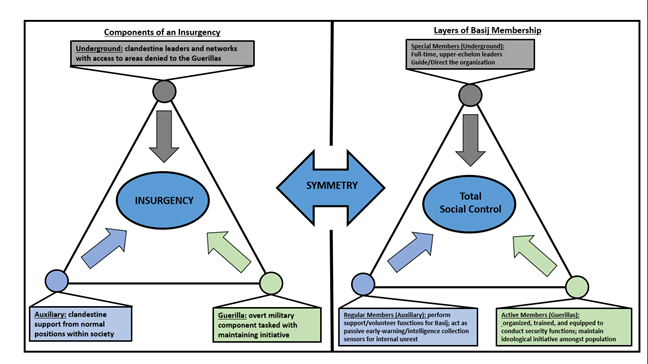

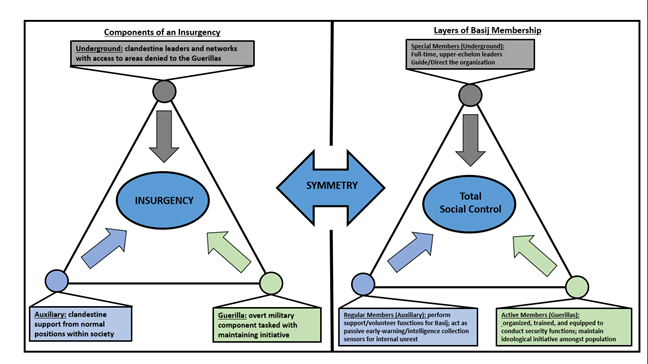

the two components of an insurgency are

Hello dear friends, thanks for choosing us. In this post on the solsarin site, we will talk about “the two components of an insurgency are”.

Stay with us.

How insurgencies end: The quest for government victory

Insurgency is currently the most prevalent type of war. However, success in irregular warfare cannot be quantified and measured with absolute certainty. This paper will examine how insurgencies end and how a government can achieve the optimum scenario, military victory. An insurgency could end in three possible ways: a (military) victory for the insurgents or the regime, a peace deal, or a stalemate. However, war constantly evolves; therefore, the above three scenarios can manifest at any time during the course of an insurgency. Therefore, the state should use a balanced mix of reforms and repression. A state must implement a situation-dependent policy that includes good governance and outside support, that ensures the welfare and security of the population, buttressed by an adequate narrative.

A peace settlement represents another exit strategy for belligerents in such wars. Quite naturally, such an option carries both risks and opportunities. Whenever a government agrees to initiate a dialogue with a militant group, the legitimacy of the latter is upgraded, and the former’s (conversely) undermined. Thus, the negotiations could potentially backfire for the government, the public opinion could punish these politicians in the ballot box, or the diehards amongst the military could even overthrow the government amid allegations for “treason.” Conversely, such negotiations can be utilized by insurgents to either exact concessions from an ostensibly “weakened government” or just “buy time” (especially after adverse developments in battle or other domains) and continue the armed struggle after a (free of enemy pressure) recovery (Byman, 2009, p. 129; Bernstein, 2012, p. 31; Duyvesteyn & Schuurman, 2011, pp. 679-679). The ultimate prize, however, renders the entire (risky) effort worthwhile. Negotiations (in good faith) could reinforce the hand of the “peace doves” versus the “hardliners” within the militant leadership and, thus open the way to a permanent cease in hostilities (Johnston, 2007, pp. 559-577; Byman, 2009, pp. 127-128).

But, how do such talks start in the first place? Usually, failures on the field of battle or transitions in the leadership (i.e., the rise to power of “peace doves”), for both belligerents, act as triggers for the initiation (or acceleration) of a peace process (Zartman, 1995, pp. 16-19). A “shock incident” (i.e., a catastrophic event such as the collapse of an external ally) (Pruitt, 2005, p. 4) and a “mutually hurting stalemate” (i.e., a deadlock in military terms) could create a “period of ripeness” (Zartman, 2001, pp. 8-18), a propitious situation for negotiations between the two sides. The meditation of an internal or external actor (mutually accepted as an “honest broker”) can, quite often, contribute positively to a peace process (Henry, 2006, pp. 60-71; Call, Cousens, 2008, pp. 1-21). As a rule of thumb, the longer an irregular conflict drags on, the bigger the prospects of a peace settlement of any variation (Mason, Weingarten & Fett, 1999, pp. 239-268).

Such negotiations can be a minefield. Often, the regime does not possess accurate information about the (actual) intentions of the rebels (information asymmetry) (Walter, 2013, pp. 664-665) and, by extension, their genuine willingness for peace; nor can the regime easily identify the party or person that can act as a reliable “spokesman” for the rebels (delegation issue) (Zartman, 1993, pp. 25-27; 1995 Ibid, p. 10). However, even when negotiations commence despite the above obstacles, the two sides cannot easily and completely reconcile their contradictory claims over a mutually sought-after prize (divisibility issues); for example, the possession of a specific city or territory (Walter, 2013; pp. 659-660; Plakoudas, 2017, p. 159). Often, hard-line factions among one or both sides act as spoilers and undermine the peace talks with their provocations (Stedman, 1997, pp. 5-53; Greenhill, Major, 2006-2007, pp. 6-40).

The most significant obstacle to peace, however, is the reluctance of both sides to honestly commit to a peace process -especially if the war, violence, and polarization have reached notoriously high levels or one side has reneged on its promises in previous times (Walter, 1999, pp. 127-155; Mattes, Savun, 2009, pp. 737-759). Therefore, it is fairly common practice for both sides (and usually, the insurgents) to continue their operations on a low tempo in order to dictate new favorable terms for a peace settlement or compel their adversary to abide by the roadmap for peace (Wagner, 2000, pp. 464-484; Reiter, 2003; pp. 27-43; Henry, 2006, pp. 60-71). However, the danger of an unwanted escalation and eventual collapse of negotiations from such operations is evident. A remedy to that problem would be a roadmap for peace with clear-cut power-sharing clauses guaranteed by a third (mutually-accepted) party (Walter, 2002, p. 92; Hartzell & Hoddie, 2003, pp. 318-332).

Since the 1980s, a pattern can be easily discerned. Before the 1980s, the majority of irregular wars were decided on the battlefield; most of them are now settled at the negotiation table (Licklider, 1995, pp. 681-690; Duyvesteyn & Schuurman, 2011, p. 667). The record, so far, is quite varied: 12% of the insurgencies ended through negotiations in favor of the regime and only 7% in favor of the rebels, whereas another 20% of them ended in a balanced way (McCormick, Horton & Harrison, 2009, p. 128). The peace treaty between Guatemala and the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG) in 1996 clearly amounted to a defeat for the insurgents in the Guatemalan Civil War. Conversely, the settlement between Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in 2005 was a victory for the later in the 2nd Sudanese Civil War. Lastly, the deal, in 2005, between Indonesia and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) yielded a balanced conclusion of the “Aceh Disturbance.”

The viability of the peace settlements, however, cannot always be assured; relapse to violence was observed in over 40% of the cases in recent years (Licklider, 1995, pp. 681-682, 684-687; Derouen, Bercovitch & Wei, 2009, pp. 103-120). For example, the peace treaty of 1970 between the Iraqi Kurds and Baghdad collapsed four years later. The survivability of peace settlements is especially difficult in cases of sectarian conflict due to the high levels of violence and polarization that such wars elicit (Kaufmann, 1996, pp. 136-175). For example, the Taif Accord ended the Lebanese Civil War but did not avert the outburst of violence entirely in this volatile country. Quite often, external powers intervene to undermine a peace deal that they deem injurious to their interests, causing a relapse to violence (Licklider, 1993, pp. 306-315). For instance, in 2017, Haftar declared the Skhirat Agreement null and void and, buoyed by the support of outside powers such as Egypt, endeavored to end the Libyan Civil War militarily. Thus, countries and organizations of collective security should intervene and act as guarantors of “positive peace.” However, these actors should insist on the establishment of non-partisan state institutions so that peace-keeping will be substituted over time by peace-building (Mason, 2007, pp. 70-77).

insurgency, term historically restricted to rebellious acts that did not reach the proportions of an organized revolution. It has subsequently been applied to any such armed uprising, typically guerrilla in character, against the recognized government of a state or country.

In traditional international law, insurgency was not recognized as belligerency, and insurgents lacked the protection customarily extended to belligerents. Herbert W. Briggs in The Law of Nations (1952) described the traditional point of view as follows:

The existence of civil war or insurrection is a fact. Traditionally, the fact of armed rebellion has not been regarded as involving rights and obligations under international law.…Recognition of the belligerency of the insurgents by the parent State or of the contestants by foreign States changes the legal situation under international law. Prior to such recognition, foreign States have a legal right to aid the parent State put down a revolt, but are under a legal obligation not to aid insurgents against the established government.

The status of the faction opposing a government was usually determined by what Charles Cheney Hyde described as “the nature and extent of the insurrectionary achievement.” If the government was able to suppress the hostile faction rapidly, the event was described as a “rebellion.” In such cases recognition of the insurgents by a third party was regarded as “premature recognition,” a form of illegal intervention. If the insurgents became a serious challenge to the government and achieved formal recognition as “belligerents,” then the struggle between the two factions became in international law the equivalent of war. Support given to the insurgents by a third party amounted to that foreign government’s participation in the war.

MORE POSTS FOR DEAR READERS:

- how to treat cat allergies in dog

- to a bird of prey what is an eyrie?

- what country is bucharest located in

- how many percentage of pure water is on earth

- square is to triangle as cube is to

After World War II the emergence of a number of Communist states and of new nations in Asia and Africa changed the established international legal doctrine on insurgency. Communist states claimed the right to support insurgents engaged in “just wars of national liberation.” The new nations resulting from decolonization in Asia and Africa after World War II supported in most cases insurgents who invoked the principle of “national self-determination.” The United States and other Western countries in turn rejected such intervention as “indirect aggression” or “subversion.” International legal consensus regarding insurgency thus broke down as the result of regional and ideological pressures.

At the same time, humanitarian considerations prompted the international community to extend protection to persons involved in any “armed conflict” regardless of its formal legal status. This was done through the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, one of four agreements drafted in August 1949. Members of “organized resistance movements” are protected if in conducting their operations they have acted in military fashion, whereas insurgents lacking formal belligerent status were not protected under traditional international law.

In the Cold War era, insurgency was treated as synonymous with a system of politico-military techniques that aimed at fomenting revolution, overthrowing a government, or resisting foreign invasion. Those who rejected the use of violence as an instrument of social and political change used the term insurgency synonymously with revolutionary war, resistance war, war of national liberation, people’s war, protracted war, partisan war, or guerrilla war, without special concern for either the objectives or the methods of the insurgents. Insurgency referred no longer only to acts of violence on a limited scale but to operations that extended to a whole country and lasted for a considerable period of time. The insurgents attempted to win popular support for the rebel cause, while the threatened government sought to counter the efforts of the rebels. In such contests military operations were closely connected with political, economic, social, and psychological means, more so than either in conventional warfare or in insurgencies of an earlier period.