who was the heaviest u.s. president?

Hi dear readers, Have you ever thought about this question “who was the heaviest u.s. president?” Today on Solsarin we’re going to answer this question.

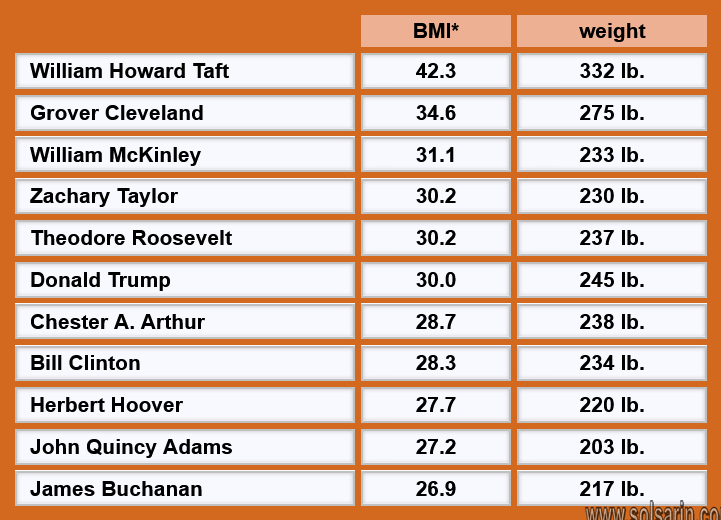

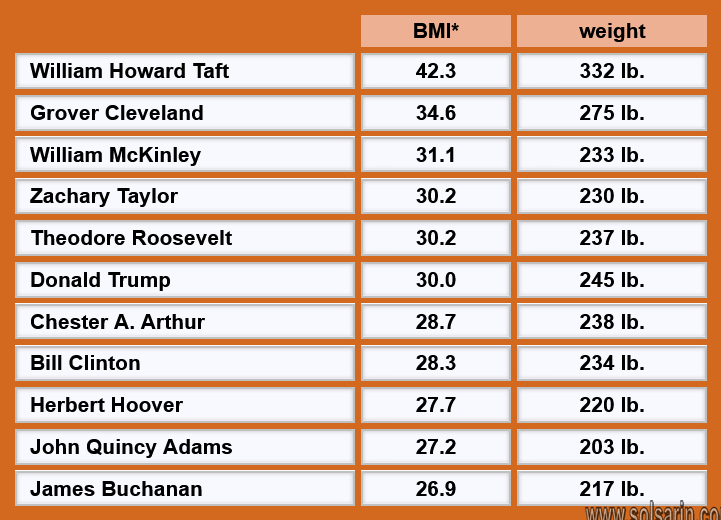

The Fattest Presidents

ordered by BMI (Body Mass Index*)

We want to talk about three of America’s heaviest presidents :

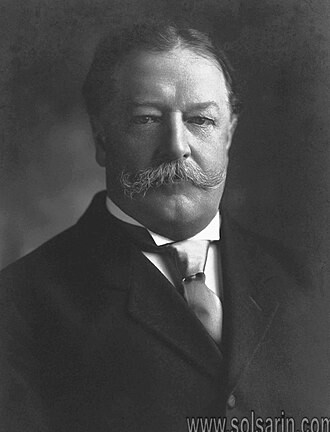

1- William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857 – March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913)

and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices.

Taft was elected president in 1908, the chosen successor of Theodore Roosevelt

but was defeated for reelection by Woodrow Wilson in 1912 after Roosevelt split the Republican vote by running as a third-party candidate.

In 1921, President Warren G. Harding appointed Taft to be chief justice, a position he held until a month before his death.

Fun Fact: William Taft gave the White House its first set of “wheels.” He had the stables converted into a garage for four cars, all ordered in 1909.

President Taft was a huge man, weighing more than 300 pounds.

A special bathtub was installed for him in the White House, big enough to hold four men.

Fast Fact: William Howard Taft: the only man to become President and then chief justice.

Biography: Distinguished jurist, effective administrator, but poor politician, William Howard Taft spent four uncomfortable years in the White House. Large, jovial, conscientious

he was caught in the intense battles between Progressives and conservatives, and got scant credit for the achievements of his administration.

Born in 1857, the son of a distinguished judge, he was graduated from Yale, and returned to Cincinnati to study and practice law.

He rose in politics through Republican judiciary appointments, through his own competence and availability

and because, as he once wrote facetiously, he always had his “plate the right side up when offices were falling.”

But Taft much preferred law to politics. He was appointed a Federal circuit judge at 34.

He aspired to be a member of the Supreme Court, but his wife, Helen Herron Taft, held other ambitions for him.

His route to the White House was via administrative posts.

President McKinley sent him to the Philippines in 1900 as chief civil administrator. Sympathetic toward the Filipinos

he improved the economy, built roads and schools, and gave the people at least some participation in government.

President Roosevelt made him Secretary of War, and by 1907 had decided that Taft should be his successor.

The Republican Convention nominated him the next year.

Taft disliked the campaign–“one of the most uncomfortable four months of my life.” But he pledged his loyalty to the Roosevelt program

popular in the West, while his brother Charles reassured eastern Republicans.

William Jennings Bryan, running on the Democratic ticket for a third time, complained that he was having to oppose two candidates

a western progressive Taft and an eastern conservative Taft.

Progressives were pleased with Taft’s election. “Roosevelt has cut enough hay,” they said; “Taft is the man to put it into the barn.”

Conservatives were delighted to be rid of Roosevelt–the “mad messiah.”

Taft recognized that his techniques would differ from those of his predecessor.

Unlike Roosevelt, Taft did not believe in the stretching of Presidential powers.

He once commented that Roosevelt “ought more often to have admitted the legal way of reaching the same ends.”

Taft alienated many liberal Republicans who later formed the Progressive Party

by defending the Payne-Aldrich Act which unexpectedly continued high tariff rates.

A trade agreement with Canada, which Taft pushed through Congress

would have pleased eastern advocates of a low tariff, but the Canadians rejected it.

He further antagonized Progressives by upholding his Secretary of the Interior, accused of failing to carry out Roosevelt’s conservation policies.

In the angry Progressive onslaught against him, little attention was paid to the fact that his administration initiated 80 antitrust suits

and that Congress submitted to the states amendments for a Federal income tax and the direct election of Senators.

A postal savings system was established, and the Interstate Commerce Commission was directed to set railroad rates.

In 1912, when the Republicans renominated Taft, Roosevelt bolted the party to lead the Progressives

thus guaranteeing the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Taft, free of the Presidency, served as Professor of Law at Yale until President Harding made him Chief Justice of the United States

a position he held until just before his death in 1930. To Taft, the appointment was his greatest honor;

he wrote: “I don’t remember that I ever was President.”

Read More Posts:

2- Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer

and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897.

Cleveland is the only president in American history to serve two nonconsecutive terms in office.

He won the popular vote for three presidential elections—in 1884, 1888, and 1892—and was one of two Democrats (followed by Woodrow Wilson in 1912)

to be elected president during the era of Republican presidential domination dating from 1861 to 1933.

In 1881, Cleveland was elected mayor of Buffalo and later, governor of New York.

He was the leader of the pro-business Bourbon Democrats who opposed high tariffs

Free Silver; inflation;imperialism; and subsidies to business, farmers, or veterans.

His crusade for political reform and fiscal conservatism made him an icon for American conservatives of the era.

Cleveland won praise for his honesty, self-reliance, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism.

He fought political corruption, patronage, and bossism. As a reformer, Cleveland had such prestige that the like-minded wing of the Republican Party

called “Mugwumps”, largely bolted the GOP presidential ticket and swung to his support in the 1884 election.

As his second administration began, disaster hit the nation when the Panic of 1893 produced a severe national depression.

It ruined his Democratic Party, opening the way for a Republican landslide in 1894

and for the agrarian and silverite seizure of the Democratic Party in 1896.

The result was a political realignment that ended the Third Party System and launched the Fourth Party System and the Progressive Era.

Cleveland was a formidable policymaker, and he also drew corresponding criticism. His intervention in the Pullman Strike of 1894 to keep the railroads moving angered labor unions nationwide in addition to the party in Illinois; his support of the gold standard and opposition to Free Silver alienated the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party. Critics complained that Cleveland had little imagination and seemed overwhelmed by the nation’s economic disasters—depressions and strikes—in his second term. Even so, his reputation for probity and good character survived the troubles of his second term. Biographer Allan Nevins wrote, “[I]n Grover Cleveland, the greatness lies in typical rather than unusual qualities.

He had no endowments that thousands of men do not have. He possessed honesty, courage, firmness, independence, and common sense. But he possessed them to a degree other men do not.”[6] By the end of his second term, public perception showed him to be one of the most unpopular U.S. presidents, and he was by then rejected even by most Democrats.[7] Today, Cleveland is considered by most historians to have been a successful leader, and has been praised for honesty, integrity, adherence to his morals and defying party boundaries, and effective leadership. He is generally ranked among the upper-mid tier of American presidents.

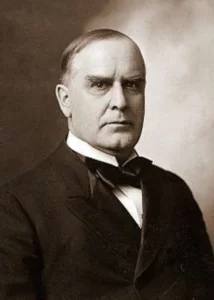

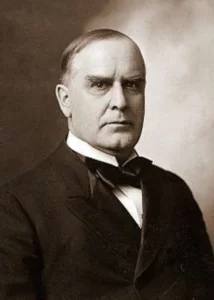

3- William McKinley

William McKinley, (born January 29, 1843, Niles, Ohio, U.S.—died September 14, 1901, Buffalo, New York), 25th president of the United States (1897–1901). Under McKinley’s leadership, the United States went to war against Spain in 1898 and thereby acquired a global empire, which included Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

Early life

McKinley was the son of William McKinley, a manager of a charcoal furnace and a small-scale iron founder, and Nancy Allison. Eighteen years old at the start of the Civil War, McKinley enlisted in an Ohio regiment under the command of Rutherford B. Hayes, later the 19th president of the United States (1877–81). Promoted second lieutenant for his bravery in the Battle of Antietam (1862), he was discharged a brevet major in 1865. Returning to Ohio, he studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1867, and opened a law office in Canton, where he resided—except for his years in Washington, D.C.—for the rest of his life.

Congressman and governor

Drawn immediately to politics in the Republican Party, McKinley supported Hayes for governor in 1867 and Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868. The following year he was elected prosecuting attorney for Stark county, and in 1877 he began his long career in Congress as representative from Ohio’s 17th district. McKinley served in the House of Representatives until 1891, failing reelection only twice—in 1882, when he was temporarily unseated in an extremely close election, and in 1890, when Democrats gerrymandered his district.

The issue with which McKinley became most closely identified during his congressional years was the protective tariff, a high tax on imported goods which served to protect American manufacturers from foreign competition. While it was only natural for a Republican from a rapidly industrializing state to favour protection, McKinley’s support reflected more than his party’s pro-business bias. A genuinely compassionate man, McKinley cared about the well-being of American workers, and he always insisted that a high tariff was necessary to assuring high wages.

As chairman of the House HouseWays and Means Committee, he was the principal sponsor of the McKinley Tariff of 1890, which raised duties higher than they had been at any previous time. Yet by the end of his presidency McKinley had become a convert to commercial reciprocity among nations, recognizing that Americans must buy products from other countries in order to sustain the sale of American goods abroad.