Do beetles have ears?

Hello. Welcome to solsarin. This post is about “Do beetles have ears? “.

Beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (/koʊliːˈɒptərə/), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 described species, is the largest of all orders, constituting almost 40% of described insects and 25% of all known animal life-forms; new species are discovered frequently, with estimates suggesting that there are between 0.9 to 2.1 million total species. Found in almost every habitat except the sea and the polar regions, they interact with their ecosystems in several ways: beetles often feed on plants and fungi, break down animal and plant debris, and eat other invertebrates. Some species are serious agricultural pests, such as the Colorado potato beetle, while others such as Coccinellidae (ladybirds or ladybugs) eat aphids, scale insects, thrips, and other plant-sucking insects that damage crops.

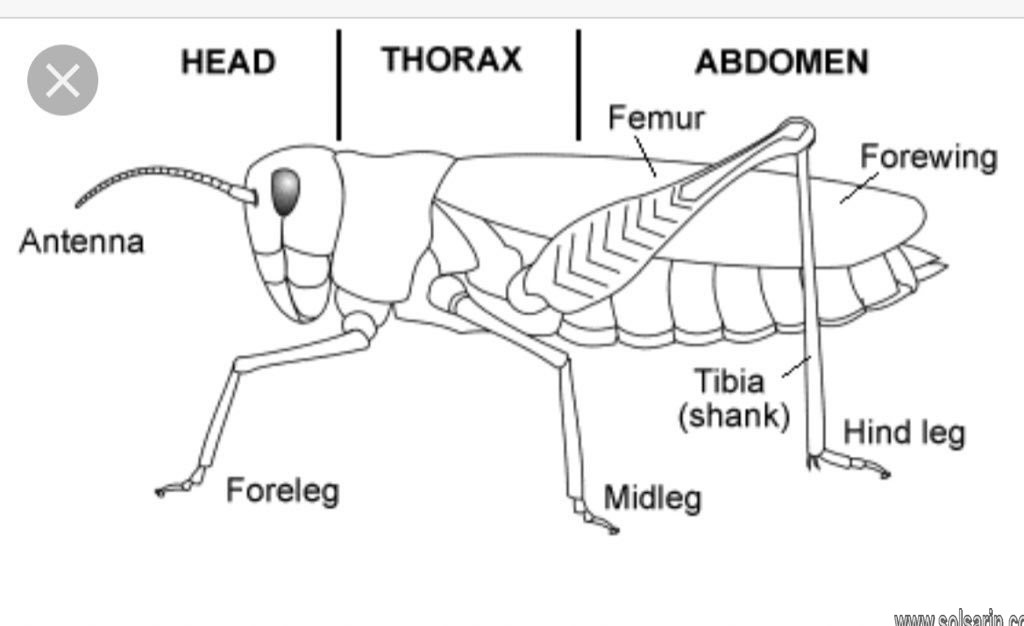

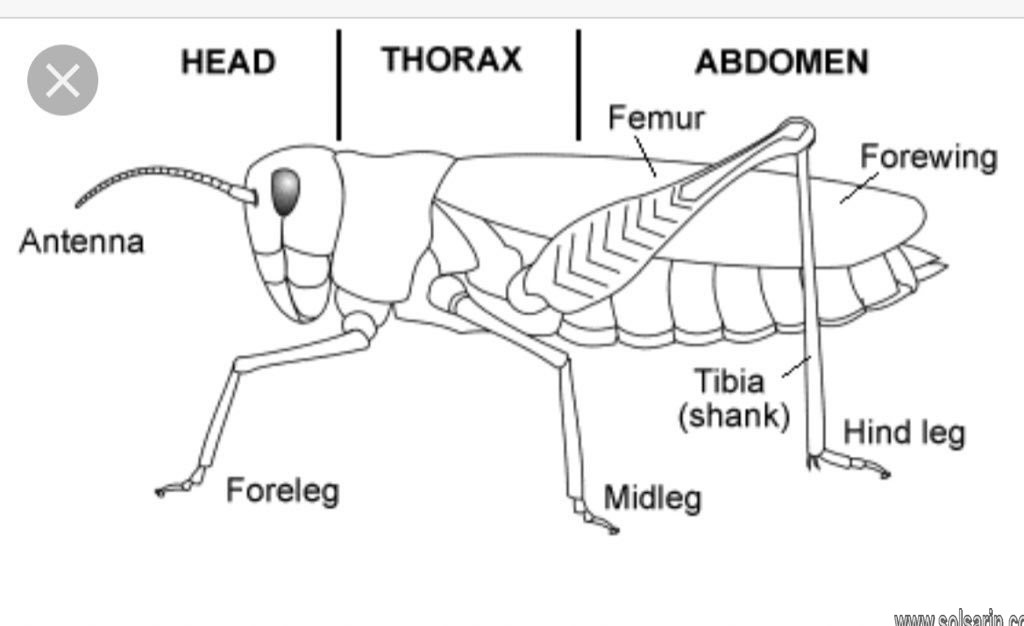

Beetles typically have a particularly hard exoskeleton including the elytra, though some such as the rove beetles have very short elytra while blister beetles have softer elytra. The general anatomy of a beetle is quite uniform and typical of insects, although there are several examples of novelty, such as adaptations in water beetles which trap air bubbles under the elytra for use while diving. Beetles are endopterygotes, which means that they undergo complete metamorphosis, with a series of conspicuous and relatively abrupt changes in body structure between hatching and becoming adult after a relatively immobile pupal stage.

colours and patterns warning

Some, such as stag beetles, have a marked sexual dimorphism. The males possessing enormously enlarged mandibles which they use to fight other males. Many beetles are aposematic, with bright colours and patterns warning of their toxicity, while others are harmless Batesian mimics of such insects. Many beetles, including those that live in sandy places, have effective camouflage.

Beetles are prominent in human culture, from the sacred scarabs of ancient Egypt to beetlewing art and use as pets or fighting insects for entertainment and gambling. Many beetle groups are brightly and attractively coloured making them objects of collection and decorative displays. Over 300 species are used as food, mostly as larvae; species widely consumed include mealworms and rhinoceros beetle larvae. However, the major impact of beetles on human life is as agricultural, forestry, and horticultural pests. Serious pests include the boll weevil of cotton, the Colorado potato beetle, the coconut hispine beetle. And the mountain pine beetle. Most beetles, however, do not cause economic damage and many, such as the lady beetles and dung beetles are beneficial by helping to control insect pests.

If you want to know about “why are bulls circumcised“, click on it.

Etymology

The name of the taxonomic order, Coleoptera, comes from the Greek koleopteros (κολεόπτερος), given to the group by Aristotle for their elytra, hardened shield-like forewings, from koleos, sheath, and pteron, wing. The English name beetle comes from the Old English word bitela, little biter, related to bītan (to bite), leading to Middle English betylle. Another Old English name for beetle is ċeafor, chafer, used in names such as cockchafer, from the Proto-Germanic *kebrô (“beetle”; compare German Käfer, Dutch kever).

Distribution and diversity

Beetles are by far the largest order of insects: the roughly 400,000 species make up about 40% of all insect species so far described. And about 25% of all animals. A 2015 study provided four independent estimates of the total number of beetle species, giving a mean estimate of some 1.5 million with a “surprisingly narrow range” spanning all four estimates from a minimum of 0.9 to a maximum of 2.1 million beetle species. The four estimates made use of host-specificity relationships (1.5 to 1.9 million), ratios with other taxa (0.9 to 1.2 million), plant:beetle ratios (1.2 to 1.3), and extrapolations based on body size by year of description (1.7 to 2.1 million).

Awesome Ears: The Weird World of Insect Hearing

In a small windowless room on a sweltering summer’s day, I find myself face-to-face with an entomological rock star. I’m at the University of Lincoln in eastern England, inside an insectary, a room lined with tanks and jars containing plastic plants and dozing insects. Before I know it, I’m being introduced to a vibrant-green katydid from Colombia.

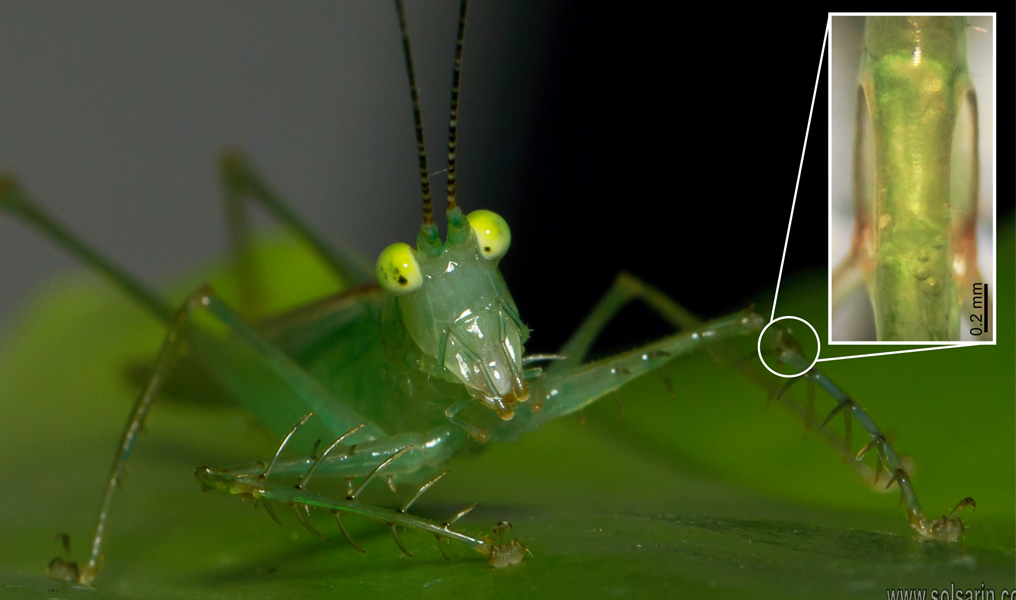

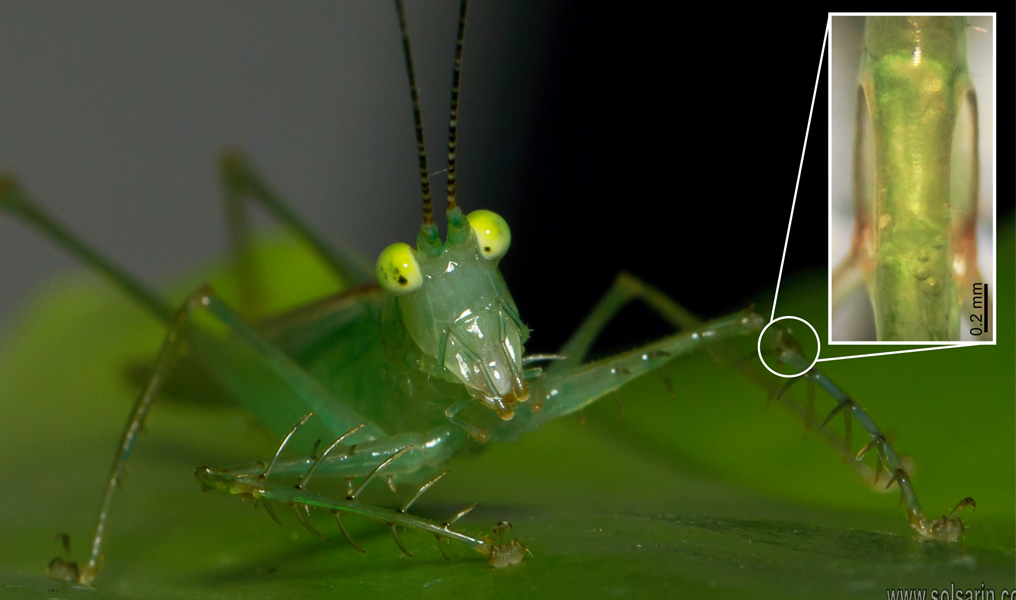

“Meet Copiphora gorgonensis,” says Fernando Montealegre-Z, discoverer of this six-legged celebrity. The name’s familiar: It’s been splashed across the world alongside photos of the insect’s golden face and miniature unicorn’s horn. The renown of this katydid rests not on its looks, though, but on its hearing. Montealegre-Z’s meticulous studies of the magnificent insect revealed that it has ears uncannily like ours, with entomological versions of eardrums, ossicles and cochleas to help it pick up and analyze sounds.

Ultrasonic click sound detection of hunting bats

Katydids—there are thousands of species—have the smallest ears of any animal, one on each front leg just below the “knee”. But their small size and seemingly strange location belie the sophisticated structure and impressive capabilities of these organs: to detect the ultrasonic clicks of hunting bats, pick out the signature songs of prospective mates, and home in on dinner. One Australian katydid has capitalized on its auditory prowess to capture prey in a very devious way. It lures male cicadas within striking distance by mimicking the female part of the cicada mating duet—a trick requiring it to recognize complex patterns of sound and precisely when to chip in.

Martin Göpfert

Curiosity piqued, I call neurobiologist Martin Göpfert at the University of Göttingen in Germany, who studies hearing in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Amazing though katydid ears are, he tells me. They’re just one of many with astonishing capabilities. Evolution has made so many attempts at shaping ears, the result is a huge diversity of structures and mechanisms. Most are hard to spot, if not invisible, and in many cases insects produce and sense sounds so far beyond our own range that we overlooked their abilities entirely. But with the advent of new tools and technologies, ever more examples are coming to light.

Sensory biologists, acoustics experts and geneticists are working together to pin down how they all work. And thanks to some of this newfound knowledge.

The antennal ear

The antennal ears are receptors (sensory cells) that detect ‘near-field’ sounds. They are not modifications of chordotonal cells. They are light-weight structures located on the antenna. Being light, they easily displaced by movement of molecules in air when the antennae vibrate. Antennal ears thus respond to the air-particle movements caused by sounds, a phenomenon that is described as particle velocity component of sound. Although new evidence seems to indicate that antennal ears may hear high frequency sounds that are far away. Research shows that antennal ears are generally efficient in hearing low frequency sounds coming from sources closer to the ears.

Do you want to know about “what does mollusca mean“? Click on it.

The Tympanal ear

Tympanal ears, by contrast, are much more than a group of receptors. Like human ears they have a sound-receiving eardrum—the tympanum—that vibrates in response to the pressure component of sound. Eardrums in insects are believed to have come about through a stepwise thinning of the cuticle. They backed by air sacs. Because the eardrums backed by air sacs, impedance-matching middle-ear structures, seen in humans are not required, allowing the auditory organ to pick up the vibrations directly from the eardrum. While this is the basic principle of tympanal ears, there are structural differences seen among insects that have these ears

Cyclopean ear

Mantids are the cheetahs of the insect world. Their forelegs are for no saintly prayers when they hold them together in front of their body; with the liberal scattering of spines on them, these folded forelegs are a hunting posture, ready for attack, to capture the prey and rip it apart for a juicy meal. But this predator king of the insect world has its own nemesis, the bat. Scientists believe that the ear in mantids developed to escape from bats.

Insect musicians: katydids, crickets

Tropical forests buzz with sounds and are a haven for acoustic ecologists. Dominating the scenario are songs of insects such as katydids and crickets. By extension, it proves that ears evolved not for evading bats but as a means of communication.

Ears in moths and butterflies

Bats are major predators of nocturnal insects, both flying and non-flying ones. They hunt insects even without echolocation, a feature one rarely hears about. But it is not just bats that insects have to worry about. There are other vertebrate predators such as reptiles, birds, mammals and amphibians that seek out insects for food. Most of the moths that visit my moth screen at my home fall prey to lizards. At Kalakad Mundanturai Tiger Reserve, a cuckoo came to feed on moths at midnight. Insects such as praying mantids and assassin bugs love to gorge on moths.

Thank you for staying with this post “Do beetles have ears? ” until the end.