byzantine art is notable for its

Hi dear readers, Solsarin in this article is talking about “byzantine art is notable for its”

Byzantine art

Byzantine art comprises the body of Christian Greek artistic products of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire.

Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise.

Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire’s culture and art for centuries afterward.

A number of contemporary states with the Byzantine Empire were culturally influenced by it without actually being part of it (the “Byzantine commonwealth”).

These included the Rus, as well as some non-Orthodox states like the Republic of Venice, which separated from the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century, and the Kingdom of Sicily, which had close ties to the Byzantine Empire and had also been a Byzantine territory until the 10th century with a large Greek-speaking population persisting into the 12th century.

Other states having a Byzantine artistic tradition, had oscillated throughout the Middle Ages between being part of the Byzantine Empire and having periods of independence, such as Serbia and Bulgaria.

Introduction

Byzantine art originated and evolved from the Christianized Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire;

The art of Byzantium never lost sight of its classical heritage.

The basis of Byzantine art is a fundamental artistic attitude held by the Byzantine Greeks who, like their ancient Greek predecessors, “were never satisfied with a play of forms alone, but stimulated by an innate rationalism, endowed forms with life by associating them with a meaningful content.”

The nature and causes of this transformation, which largely took place during late antiquity, have been a subject of scholarly debate for centuries.

Although this point of view has been occasionally revived, most notably by Bernard Berenson, modern scholars tend to take a more positive view of the Byzantine aesthetic.

Alois Riegl and Josef Strzygowski, writing in the early 20th century, were above all responsible for the revaluation of late antique art.

Riegl saw it as a natural development of pre-existing tendencies in Roman art, whereas Strzygowski viewed it as a product of “oriental” influences.

Notable recent contributions to the debate include those of Ernst Kitzinger, who traced a “dialectic” between “abstract” and “Hellenistic” tendencies in late antiquity, and John Onians, who saw an “increase in visual response” in late antiquity, through which a viewer “could look at something which was in twentieth-century terms purely abstract and find it representational.”

In any case, the debate is purely modern: it is clear that most Byzantine viewers did not consider their art to be abstract or unnaturalistic.

As Cyril Mango has observed, “our own appreciation of Byzantine art stems largely from the fact that this art is not naturalistic; yet the Byzantines themselves, judging by their extant statements, regarded it as being highly naturalistic and as being directly in the tradition of Phidias, Apelles, and Zeuxis.

Read More Posts:

A beginner’s guide to Byzantine Art

To speak of “Byzantine Art” is a bit problematic, since the Byzantine empire and its art spanned more than a millennium and penetrated geographic regions far from its capital in Constantinople.

Thus, Byzantine art includes work created from the fourth century to the fifteenth century and encompassing parts of the Italian peninsula, the eastern edge of the Slavic world, the Middle East, and North Africa.

So what is Byzantine art, and what do we mean when we use this term?

Middle Byzantine (c. 850–1204)

Late Byzantine (c. 1261–1453)

Early Byzantine (c. 330–750)

Christianity flourished and gradually supplanted the Greco-Roman gods that had once defined Roman religion and culture.

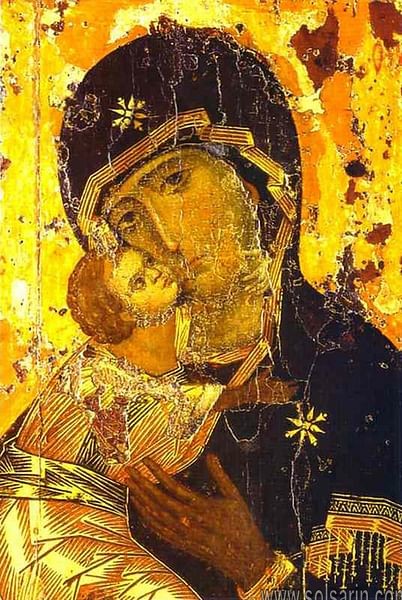

Icons, such as the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (left), served as tools for the faithful to access the spiritual world—they served as spiritual gateways.

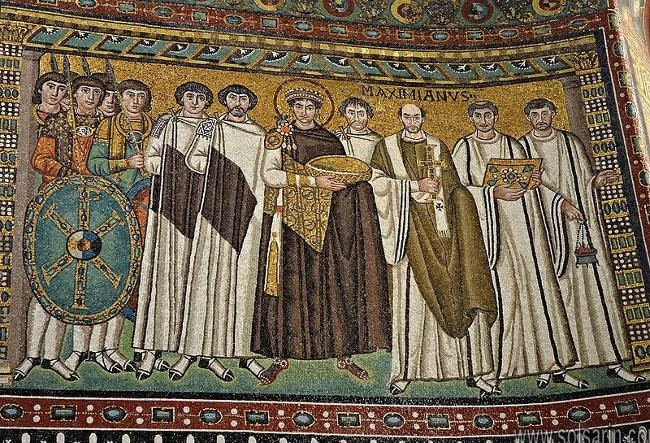

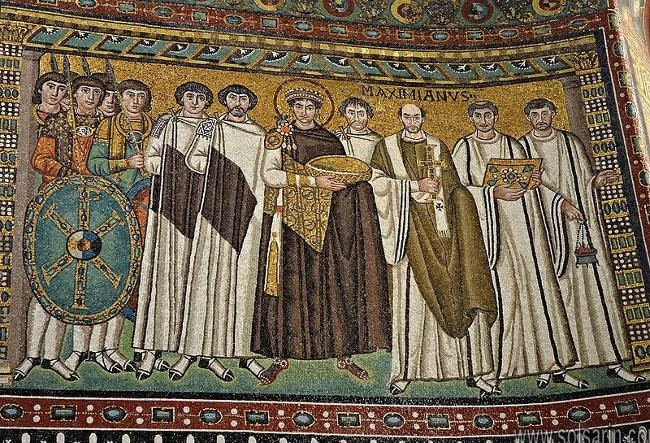

In this work, ethereal figures seem to float against a gold background that is representative of no identifiable earthly space.

By placing these figures in a spiritual world, the mosaics gave worshippers some access to that world as well.

At the same time, there are real-world political messages affirming the power of the rulers in these mosaics. In this sense, the art of the Byzantine Empire continued some of the traditions of Roman art.

Middle Byzantine (c. 850–1204)

Fortunately for art history, those in favor of images won the fight, and hundreds of years of Byzantine artistic production followed.

There were some significant changes in the empire, however, that brought about some change in the arts. First, the influence of the empire spread into the Slavic world with the Russian adoption of Orthodox Christianity in the tenth century.

Like the sixth-century icon discussed above (Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George), it helped the viewer gain access to the heavenly realm.

Late Byzantine (c. 1261– 1453)

Crusaders from Western Europe invaded and captured Constantinople in 1204, temporarily toppling the empire in an attempt to bring the eastern empire back into the fold of western Christendom.

(By this point Christianity had divided into two distinct camps: eastern [Orthodox] Christianity in the Byzantine Empire and western [Latin] Christianity in the European west.)

Seventh-century crisis

The Age of Justinian was followed by a political decline since most of Justinian’s conquests were lost and the Empire faced an acute crisis with the invasions of the Avars, Slavs, Persians, and Arabs in the 7th century.

The church of Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki was rebuilt after a fire in the mid-seventh century. The new sections include mosaics executed in a remarkably abstract style. The church of the Koimesis in Nicaea (present-day Iznik), destroyed in the early 20th century but documented through photographs, demonstrates the simultaneous survival of a more classical style of church decoration. The churches of Rome, still a Byzantine territory in this period, also include important surviving decorative programs, especially Santa Maria Antiqua, Sant’Agnese Fuori le Mura, and the Chapel of San Venanzio in San Giovanni in Laterano. Byzantine mosaicists probably also contributed to the decoration of the early Umayyad monuments, including the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus.

Important works of luxury art from this period include the silver David Plates, produced during the reign of Emperor Heraclius, and depicting scenes from the life of the Hebrew king David. The most notable surviving manuscripts are Syriac gospel books, such as the so-called Syriac Bible of Paris. However, the London Canon Tables bear witness to the continuing production of lavish gospel books in Greek.

The period between Justinian and iconoclasm saw major changes in the social and religious roles of images within Byzantium. Proskynesis before images is also attested in texts from the late seventh century. These developments mark the beginnings of a theology of icons.

At the same time, the debate over the proper role of art in the decoration of churches intensified. Three canons of the Quinisext Council of 692 addressed controversies in this area: prohibition of the representation of the cross on church pavements (Canon 73), prohibition of the representation of Christ as a lamb (Canon 82), and a general injunction against “pictures, whether they are in paintings or in what way soever, which attract the eye and corrupt the mind and incite it to the enkindling of base pleasures” (Canon 100).

Thank you for being with us.