emperor penguin father

Hi dear friends, solsarin in this article is talking about “emperor penguin father”.

we are happy to have you on our website.

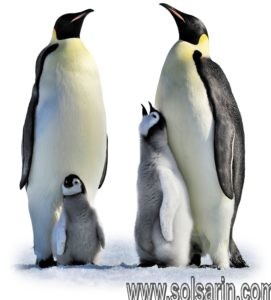

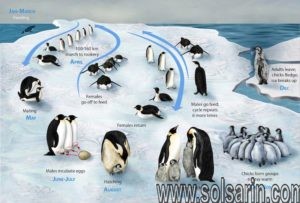

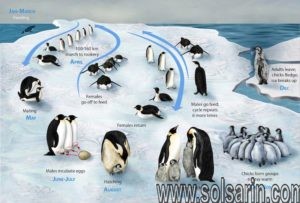

These flightless birds breed in the winter. After a courtship of several weeks, a female emperor penguin lays one single egg then leaves! Each penguin egg’s father balances it on his feet and covers it with his brood pouch, a very warm layer of feathered skin designed to keep the egg cozy. There the males stand, for about 65 days, through icy temperatures, cruel winds, and blinding storms.

Finally, after about two months, the females return from the sea, bringing food they regurgitate, or bring up, to feed the now hatched chicks. The males eagerly leave for their own fishing session at sea, and the mothers take over care of the chicks for a while.

Emperor penguins are good dads

We know there are some awesome dads out there among you humans. But the nominees for best dad must surely include emperor penguin males, who go to extraordinary extremes for their offspring, enduring bitter cold and darkness during winter on Earth’s coldest continent, Antarctica. It’s winter in Antarctica now. If you could visit, you’d find emperor penguin males gathered in colonies near the coast. They’re tightly huddled together to stay warm in temperatures that can dip as low as -40 degrees F (-40 degrees C), with winds as strong as 90 miles per hour (144 km/ hour). For the next two months, these devoted dads will each incubate a single egg that holds his offspring. Each dad will also care for his chick when it first hatches. Penguin dads do all this while surviving only on fat reserves from the previous summer.

Emperor Penguins: Good Dads, but Less Dedicated Than You May Have Though

“Almost all the studies about winter breeding have been conducted from the research station Dumont D’Urville, which is about 100 meters away from a colony,” he said. That colony, which was prominently featured in “March of the Penguins,” is also 100 kilometers from the ice edge, making it impossible for penguins that breed there to take breaks for fishing.

The colony that Dr. Kooyman observed was farther south than Dumont D’Urville, and was located only about 10 kilometers from the ice edge. Thus the authors suggest that the length of a fast depends largely on the breeding colony’s proximity to water. The male emperor penguins in Cape Washington probably fast for about 65 days, they estimated.

Additionally, the discovery that penguins — who are believed to be visual hunters — can successfully hunt in the dark may be good news for a species that is contending with loss of habitat because of a warming planet.

Penguins and Their Chicks: Super-Parents

A common misconception about penguin parenting, instigated by polar explorers in the 1960s, was that penguins regularly deserted their chicks. It was believed that they deliberately starved their chicks in order to force them to leave the breeding colony. This was founded on observations that the chicks of King Penguins (Aptenodytes patagonica) weighed more than adult birds and lost this weight prior to fledging. The desertion theory was subsequently generalised to other penguin and seabird species such as Albatrosses1.

Reproductive effort is a balance between the benefit of increasing offspring survival and costs, including mortality, of the parent. Any increase in parental care must therefore be finely weighed against the price paid. Fundamentally, this boils down to the harsh question: Are they worth feeding?

There are many parenting strategies for successful breeding

Rabbits often produce one litter a month, turtles yield hundreds of hatchlings and provide no parental care, Robins lay 3-4 clutches per year, about half of the chicks do not survive. Penguins tend to go for the opposing parenting strategy of “putting all your eggs in one basket”. And often there is only one egg.

Far from deserting their young, penguins are super-parents. Compared with most sea-birds, penguins have a very long pre-fledge duration; from 56 days in the Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) to a staggering fifteen months in the King Penguin. Penguin parental care can be divided into two periods. During the guard phase, penguin parents brood the chicks intensively, the female often returns to the sea to forage during this period, which can last up to 37 days. In the next phase the chicks form tight groups, or creches as they’re called1.

For King Penguin parents, each fledgling represents a huge investment. They first breed when they are around three years old. The parents spend one summer and two winters raising their young. The chicks’ weight loss, as observed by the explorers, can be explained by fluctuations in food availability. King Penguin chicks pile on the calories, lay down fat deposits and balloon to their maximum weight at four months old. A second peak occurs at around ten months. This enables them to survive long periods without food when their parents are foraging. King Penguins are serially monogamous with both parents sharing all hatching and rearing duties. They cannot raise a chick every year which explains why eggs as well as quite large chicks can be seen at the same time in King Penguin colonies2.

Penguin parents are even featured in movies

The astonishing parental care provided by the Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) has been popularised by films such as March of the Penguins and Warner Brothers’ Happy Feet. The female lays a single egg that is incubated by the male during the long Antarctic winter. A great deal of the 65-day incubation period is spent in darkness. Standing for weeks, balancing an egg on their feet, with no food, in temperatures down to minus 40 Celsius must be the epitome of good parenting. The female devotes this time to replenishing her food reserves in the open sea. On her return, these penguin parents take turns foraging at sea and caring for the chick in the colony. They are truly long-distance commuters taking foraging trips of one to three weeks averaging over 650 km per trip. They go to great lengths, literally and metaphorically, to care for their young.

The chicks need to gain significant reserves, particularly in the month prior to fledging. A study looking at the diving behaviour of adult Emperor Penguins provisioning chicks during this period, documented some record-breaking feats. They are the deepest diving of all the penguins with dives of over 500m logged. Many dives were well over ten minutes in duration, with the average number reaching more than 200 per day3.

FACTS ABOUT EMPEROR PENGUINS

To survive in such low temperatures, these brilliant birds have special adaptations – they have large stores of insulating body fat and several layers of scale-like feathers that protect them from icy winds. They also huddle close together in large groups to keep themselves, and each other, warm.

5. Around April every year (the start of the Antarctic winter) emperor penguins meet to breed on the thick Antarctic ice. By the time the female lays her egg (usually around June), she”s worked up a big appetite! She passes the egg to the male before journeying up to 80km to the open ocean where she can feed her hungry tummy on fish, squid and krill.

. During this time, the males are in charge of keeping the egg safe and warm in the breeding ground. They do this by balancing the egg on their feet and covering it with feathered skin, called a ‘brood pouch’. It takes about two months for the eggs to hatch.

7. The females return in July, bringing with them food in their bellies which they regurgitate (or throw up) for the chicks to eat. The females now take over babysitting duty, leaving the males to head to the ocean for their own fishing session.