what caused the death of marie curie?

Hi everyone, thank you for choosing us. have you ever thought about this question “what caused the death of marie curie? ”.

today on the solsarin site we are going to answer this question.

Stay with us.

Thank you for your choice.

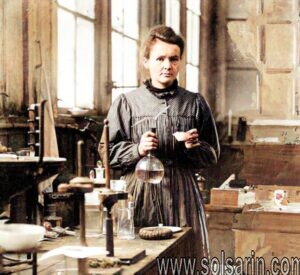

Marie Curie On 4 July 1934, at the Sancellemoz Sanatorium in Passy, France at the age of 66, died. The cause of her death was given as aplastic pernicious anaemia, a condition she developed after years of exposure to radiation through her work.

She left two daughters, Irene (born 1898) and Eve (born 1904).

Irene, like her mother, entered the field of scientific research and, with her husband Frederic Joliot, worked on the nucleus of the atom and together were awarded a Nobel Prize and credited with the discovery of artificial radiation. Irene too died of a radiation-related illness – leukaemia – in 1956.

Eve became a journalist and writer. Irene’s daughter Dr Hélène Langevin-Joliot (born 1927) also pursued a career in nuclear physics and became research emeritus of the National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris.

The first woman awarded a place in the Pantheon for her own achievements was Marie Curie .

Marie Curie’s life as a scientist was one which flourished because of her ability to observe, deduce and predict. She is also arguably the first woman to make such a significant contribution to science.

Early life

Because her father, a teacher of mathematics and physics, lost his savings through bad investment, she had to take work as a teacher and, at the same time, took part clandestinely in the nationalist “free university,” reading in Polish to women workers. At the age of 18 she took a post as governess, where she suffered an unhappy love affair.

From her earnings she was able to finance her sister Bronisława’s medical studies in Paris, with the understanding that Bronisława would in turn later help her to get an education.

Madame Curie’s Passion

The physicist’s dedication to science made it difficult for outsiders to understand her, but a century after her second Nobel prize, she gets a second look

When Marie Curie came to the United States for the first time, in May 1921, she had already discovered the elements radium and polonium, coined the term “radio-active” and won the Nobel Prize—twice. But the Polish-born scientist, almost pathologically shy and accustomed to spending most of her time in her Paris laboratory, was stunned by the fanfare that greeted her.

She attended a luncheon on her first day at the house of Mrs. Andrew Carnegie before receptions at the Waldorf Astoria and Carnegie Hall. She would later appear at the American Museum of Natural History, where an exhibit commemorated her discovery of radium.

The American Chemical Society, the New York Mineralogical Club, cancer research facilities and the Bureau of Mines held events in her honor.

Later that week, 2,000 Smith College students sang Curie’s praises in a choral concert before bestowing her with an honorary degree. Dozens more colleges and universities, including Yale, Wellesley and the University of Chicago, conferred honors on her.

Death of Pierre and second Nobel Prize

The sudden death of Pierre Curie (April 19, 1906) was a bitter blow to Marie Curie, but it was also a decisive turning point in her career: henceforth she was to devote all her energy to completing alone the scientific work that they had undertaken.

On May 13, 1906, she was appointed to the professorship that had been left vacant on her husband’s death; she was the first woman to teach in the Sorbonne.

Throughout World War I, Marie Curie, with the help of her daughter Irène, devoted herself to the development of the use of X-radiography.

Later work

In 1921, accompanied by her two daughters, Marie Curie made a triumphant journey to the United States, where President Warren G. Harding presented her with a gram of radium bought as the result of a collection among American women. She gave lectures, especially in Belgium, Brazil, Spain, and Czechoslovakia.

She was made a member of the International Commission on Intellectual Co-operation by the Council of the League of Nations. In addition, she had the satisfaction of seeing the development of the Curie Foundation in Paris and the inauguration in 1932 in Warsaw of the Radium Institute, of which her sister Bronisława became director.

The existence in Paris at the Radium Institute of a stock of 1.5 grams of radium in which, over a period of several years, radium D and polonium had accumulated made a decisive contribution to the success of the experiments undertaken in the years around 1930 and in particular of those performed by Irène Curie in conjunction with Frédéric Joliot, whom she had married in 1926 (see Joliot-Curie, Frédéric and Irène).

Her work

the resultant stockpile was an unrivaled instrument until the appearance after 1930 of particle accelerators.

The existence in Paris at the Radium Institute of a stock of 1.5 grams of radium in which, over a period of several years, radium D and polonium had accumulated made a decisive contribution to the success of the experiments undertaken in the years around 1930 and in particular of those performed by Irène Curie in conjunction with Frédéric Joliot, whom she had married in 1926 (see Joliot-Curie, Frédéric and Irène).

This work prepared the way for the discovery of the neutron by Sir James Chadwick and, above all, for the discovery in 1934 by Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie of artificial radioactivity.

Pitchblende

Pitchblende, amorphous, black, pitchy form of the crystalline uranium oxide mineral uraninite (q.v.); it is one of the primary mineral ores of uranium, containing 50–80 percent of that element.

Three chemical elements were first discovered in pitchblende: uranium by the German chemist Martin Klaproth in 1789, and polonium and radium by the French scientists Pierre and Marie Curie in 1898. Deposits, frequently in association with uraninite or with secondary uranium minerals, are known in Congo (Kinshasa); the Czech Republic; England; the Northwest Territories and Saskatchewan in Canada; and Arizona, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, and Utah in the United States.

Marie Curie the scientist

Marie Curie is remembered for her discovery of radium and polonium, and her huge contribution to finding treatments for cancer. This work continues to inspire our charity’s mission to help people and their families living with a terminal illness make the most of the time they have together by delivering expert care, emotional support and research.

Humble beginnings

Born Maria Skłodowska on 7 November 1867 in Warsaw, Poland, she was the youngest of five children of poor school teachers.

After her mother died and her father could no longer support her she became a governess, reading and studying in her own time to quench her thirst for knowledge. She never lost this passion.

To become a teacher – the only alternative which would allow her to be independent – was never a possibility because a lack of money prevented her from a formal higher education. However, when her sister offered her lodgings in Paris with a view to going to university, she grasped the opportunity and moved to France in 1891.

She immediately entered Sorbonne University in Paris where she read physics and mathematics – she had naturally discovered a love of the subjects through her insatiable appetite for learning.

Work on radioactivity and discoveries

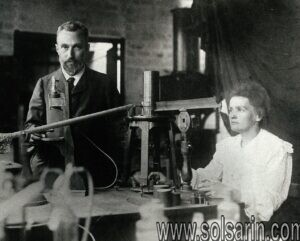

The Curies became research workers at the School of Chemistry and Physics in Paris and there they began their pioneering work into invisible rays given off by uranium – a new phenomenon which had recently been discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel.

Marie also noticed that samples of a mineral called pitchblende, which contains uranium ore, were a great deal more radioactive than the pure element uranium.

Further work convinced her the very large readings she was getting could not be caused by uranium alone – there was something else in the pitchblende.

Marie was convinced she had found a new chemical element – other scientists doubted her results.

Pierre and Marie Curie set about working to search for the unknown element. Eventually, they extracted a black powder 330 times more radioactive than uranium, which they called polonium . Polonium was a new chemical element, atomic number 84.

Marie Curie Nobel Prize

During the First World War, Marie Curie worked to develop small, mobile X-ray units that could be used to diagnose injuries near the battlefront. As Director of the Red Cross Radiological Service, she toured Paris, asking for money, supplies and vehicles which could be converted.

In October 1914, the first machines, known as “Petits Curies”, were ready, and Marie set off to the front.

The technology Marie Curie developed for the “Petits Curies” is similar to that used today in the fluoroscopy machine at our Hampstead hospice.

She was also the recipient of many honorary degrees from universities around the world.

Why we’re named after Marie Curie

A successful name in the field of science, Marie Curie allowed her name to be used by the Marie Curie Hospital in north London. Opened in 1930, it was staffed entirely by women to treat female cancer patients using radiology. It also had research facilities.

After the Marie Curie Hospital was more or less destroyed in 1944 by a bomb, a group of people decided to re-establish the hospital as a charity under Marie Curie’s name, rather than as part of the new NHS. This marked the start of the hospital’s development into a charity to support cancer patients.

Now, in the 21st century, Marie Curie is a major UK charity for people living with any terminal illness, not just cancer, and their families. We offer expert care, guidance and support to help them get the most from the time they have left. In 2015, Marie Curie’s granddaughter, Hélène Langevin-Joliot, visited our Hampstead hospice and talked about her grandmother’s legacy.

We are proud to have this great scientist as our namesake.