Eating sandhill crane

Hello friends. We are back with a delicious subject in solsarin. This is about “eating sandhill crane”. Please comment at the end of the text.

How to Cook Sandhill Crane

Setting up your Big Green Egg or Kamado grill

Fire up your charcoal quickly with a JJGeorge Grill Torch and level it off at around 300 degrees. Throw a couple of soaked hickory chunks into the charcoal to give the meat a light smokey flavor.

We are going to cook the breasts indirectly on cedar planks, so install your plate setter or other method of indirect heat if your are not using a Kamado grill. Also, now is a good time to soak your cedar planks in water if you haven’t done so already.

Prep

Make sure to soak the breasts for 24-48 hours in a half vinegar and half water mixture to draw the blood out of the meat. Once this is done, rinse it off and dry with a paper towel. We have two one pound Crane breasts and we will be using the same cooking method for both. However, we are going to season and present them differently to see what pairs best with the Sandhill Crane meat.

Chimichurri Sauce Recipe

1/2 cup – finely chopped fresh Italian parsley

1/2 cup – olive oil

2 tablespoons of white wine vinegar

salt and pepper to taste

Sandhill Cranes: Tastes Like Pork?

Sandhill cranes are not big fish eaters, so they’re not in competition with fishermen or fish farmers. The cranes are basically opportunistic herbivores, living off whatever plants or seeds are available at the time; they can manage to find food in drier upland areas as well as shallow wetlands.

Sandhill cranes dine on wild berries, seeds of many kinds, and when the possibility presents itself, small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates such as snails and insects. What actually brings them into conflict with man, particularly farmers, is their decided taste for cultivated foods. Sandhills frequently target recently planted corn and wheat fields, much like cormorants raid the densely stocked catfish ponds in the South in search of an easy meal.

To protect their fields, farmers in Wisconsin are requesting the creation of legal hunting seasons for sandhill cranes. More than a dozen states, with more in the offing, have established seasons, bag limits and takes for this once rare bird. Unlike cormorants, however, the flesh of sandhill cranes is edible and is reported by hunters to taste much like pork chops, so the birds are not merely killed and composted, but are also consumed.

Regardless of whether the carcasses are destined for the compost or the dinner table, it seems, at best, inefficient to spend decades reviving a rare, threatened species only to turn around and put it in hunters’ sights. What is really ignored here is the question of why the birds feed at agricultural sites rather than at open upland ranges or food-rich shallow wetlands. The one-word answer is habitat. Every day more and more open land is taken out of the natural food chain and converted from prairie or open range or upland habitat or wetland to real estate – development or reclamation projects – restricting the bird’s range, driving it into direct conflict with humans.

In science fiction literature and physics thought experiments it’s common to postulate what happens when human subjects are locked in suspended animation and time goes on without them. When they awaken the world has changed and there is no place for them in the future. The return of nearly-extinct species sometimes falls into this type of scenario.

There often comes a point when threatened wildlife species regain some of their original stature, attempt to re-colonize former territories and expand into new ones, but during the decades of their absence people forgot what they were, how plentiful their numbers had been, and their place in the ecosystem. In that future, the returning wildlife has lost its claim to respectable habitat and moves into territory appropriated by humans in its absence, setting the stage once again for lethal control measures of “overabundant” species, even the ones that taste like pork.

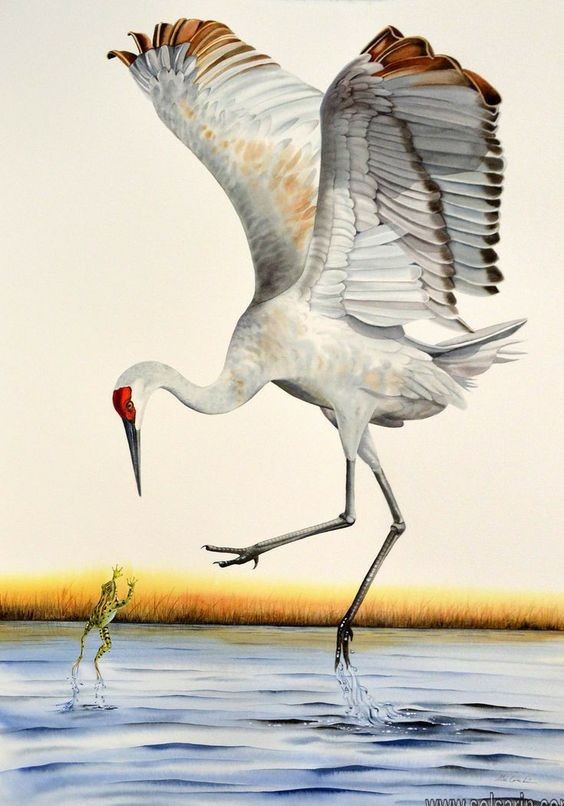

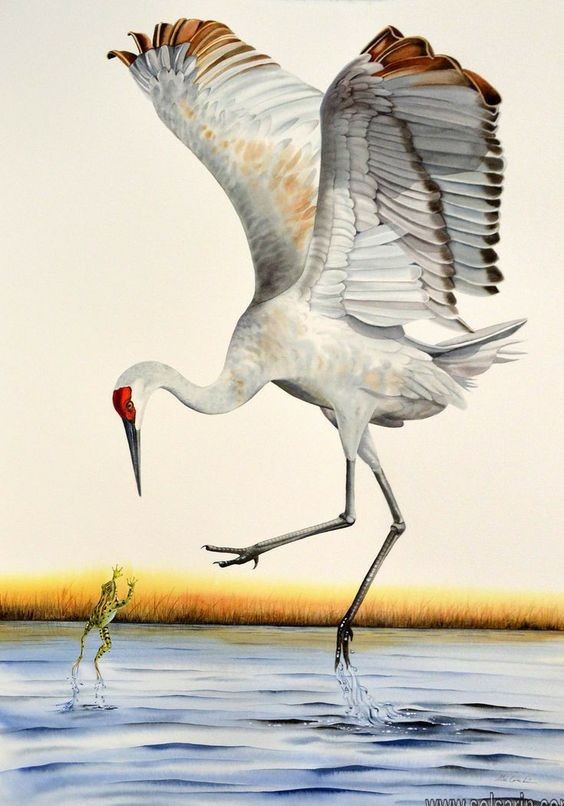

Sandhill crane

The sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis) is a species of large crane of North America and extreme northeastern Siberia. The common name of this bird refers to habitat like that at the Platte River, on the edge of Nebraska’s Sandhills on the American Great Plains. This is the most important stopover area for the nominotypical subspecies, the lesser sandhill crane (A. c. canadensis), with up to 450,000 of these birds migrating through annually.

Habits and Lifestyle

Sandhill cranes are diurnal and partially migratory. The southern populations stay near their breeding sites all year, but the northern populations winter in the south. They usually live in pairs and family groups. They sometimes join up with non-mated cranes in survival groups, to roost and feed together. When an avian predator approaches, the sandhill crane flies at it, kicking it with its feet. When the predator is a mammal, it will move towards it, with its wings spread, and points its bill at it. If it is not scared off, the crane then attacks, hissing, stabbing with its bill and kicking with its feet. These cranes communicate mainly by means of vocalizations and physical displays. Adults can make more than a dozen different calls, which have been described as types of “trills”, “purrs” and “rattles”.

Diet and Nutrition

Sandhill cranes are omnivorous, eating cultivated grains such as wheat, corn, and sorghum, when they are available. In the north, a wider variety of food is consumed, including berries, insects, small mammals, snails, reptiles, and amphibians.

Mating Habits

Sandhill cranes are monogamous. Breeding pairs usually stay together for life, maintaining their bond by performing displays of courtship, remaining near to each other and calling in unison. In populations that do not migrate, eggs are laid any time from December to August. The migratory sandhill cranes usually lay in April and May. The adults both build the nest, with plant material from their surrounding area. 1 to 3 eggs are laid and both parents incubate them, for 29 to 32 days. Chicks are precocial, being covered in down when they hatch, with eyes open and able to exit their nest within 24 hours. The chicks are brooded for as long as 3 weeks after they hatch. The parents feed the young intensively during the first few weeks, with decreasing frequency until the chicks reach independence at around 9 or 10 months. The young can begin breeding from between 2 and 7 years of age.

What are their nesting habits?

Sandhill Cranes nest among marsh vegetation in shallow water up to 3 inches (7cm) deep, or they’ll sometimes nest on dry ground close to water.

The male and the female will build their nests, made of plant material pulled up from around the site. The nest may be built up from the bottom, or it may be floating or anchored to standing plants.

What Do Sandhill Cranes Eat?

As omnivores, sandhill cranes eat a variety of food that include plants, seeds, nuts, grains, roots, crops, fruits, insects, snails, snakes, lizards, frogs, fish, rodents, and birds.

Sandhill cranes prefer plants when they are readily and widely available, but they are opportunistic feeders, so their food selection can vary depending on what choices are available for them.

As sandhill cranes prefer vegetation, they eat these foods as primary part of their diet:

- Bread

- Fruits

- Peanuts

- Berries

- Sunflower seeds

- Bird seeds

- Plant tubers

- Grains

- Roots

- Corn

- Cottonseed

- Wheat

- Acorns

- Nuts

- Sorghum

- Cultivated crops

Sandhill cranes dig and poke with their bills in search of seeds, berries, and roots. When preparing for migration, sandhill cranes rely heavily on waste corn to supplement their nutrition.

What is the Sandhill Cranes’ favorite food?

It is hard to know if the sandhill crane favors one food source over all the others.

However, some meals – plant tubers, berries, grains, earthworms, frogs, and crayfish – seem to be more highly sought after than others.

What do Sandhill Cranes eat in the wild?

Sandhill cranes are omnivores and, thus, have a wide-ranging diet that includes plants and animals. The birds frequently forage for cultivated or naturally occurring seeds, grain, and berries. They also enjoy various animal life, including insects, worms, mice, small birds, frogs, crayfish, snakes, and lizards.

Sandhill Crane Hunting Techniques

Sandhill cranes are hunted much like geese, as they typically roost in marshy, protected areas, and will leave daily to feed in agricultural fields. Here, hunters will set up in these fields and do their best to conceal themselves in layout blinds. This concealment is of utmost importance, as cranes have extremely good eyesight, and can pick off a hunter from way beyond shooting range. In addition to concealment, hunters will use a decoy spread that is typically made up of between 4 and 6 dozen full-body crane decoys. Again, the crane’s strong eyesight requires that decoys be extremely realistic, with some hunters going as far as to use taxidermied cranes in their spreads. Finally, hunters will use calls to add realism to their spread and help bring birds into range.

Cranes can be dangerous when wounded. Because of this, make sure birds are dead before sending out your dog or attempting to grab them in order to avoid any beak related injuries.

Despite the cranes large stature, their long necks make them vulnerable and easy to knock down. Because of this, shot sizes of #2 or BB are usually adequate. In addition, their keen eyesight can make decoying the birds difficult, so tighter choke patterns may help you take them from a greater distance, as well as key in on their head and neck.